New Acquisition: John Flamsteed's Historia Coelestis

Residents of the Greenwich Hospital were treated to an extraordinary sight in late April of 1716. Overlooking the hospital, on Greenwich Hill, stood the Royal Observatory, next to which burned a large fire, fueled by 13,500 sheets of printed paper, pages from a book ostensibly by the resident of the Observatory - John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal. What was he burning? His printed catalog of astronomical observations and positions made by Flamsteed and his assistants at the Observatory.

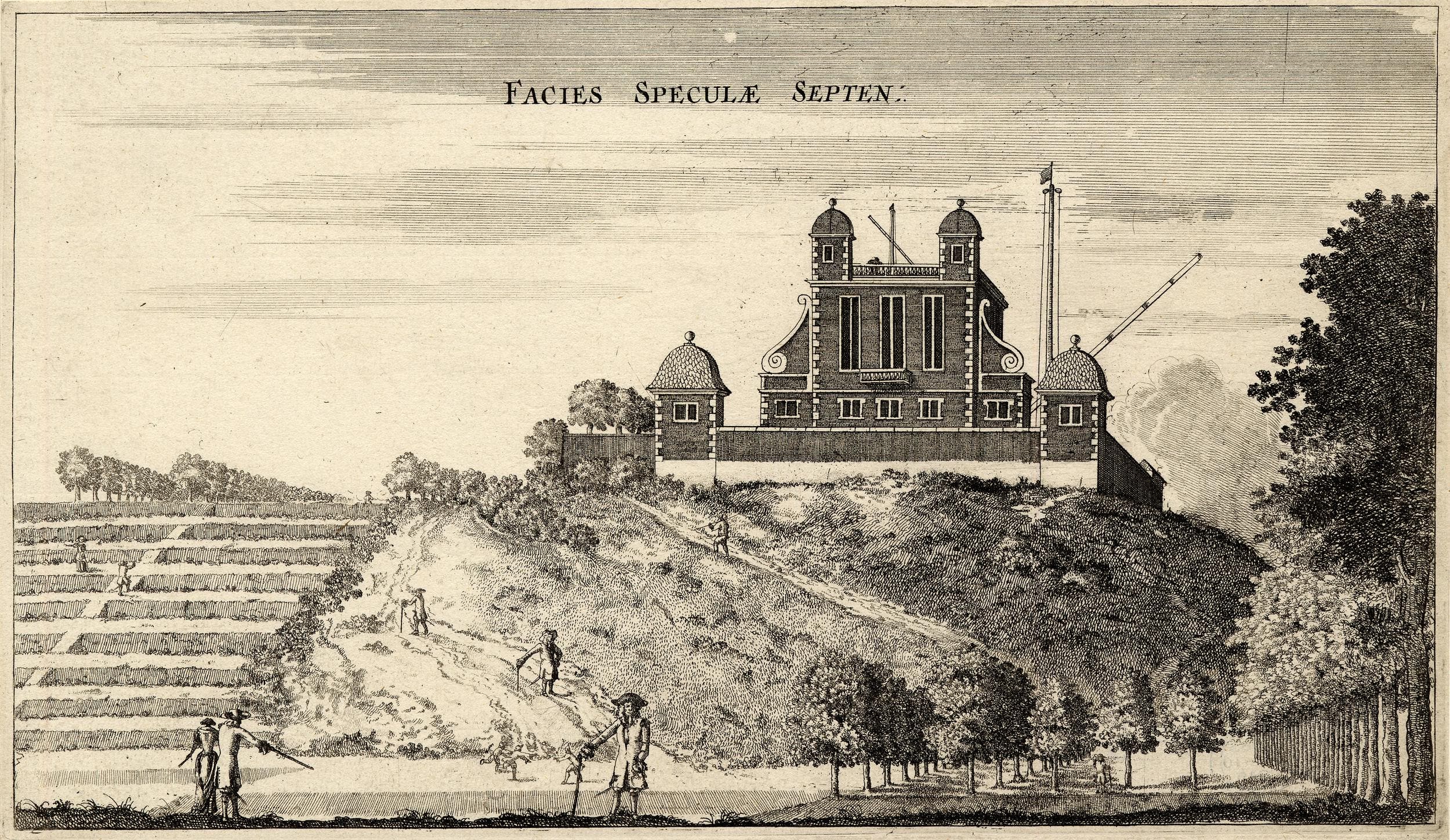

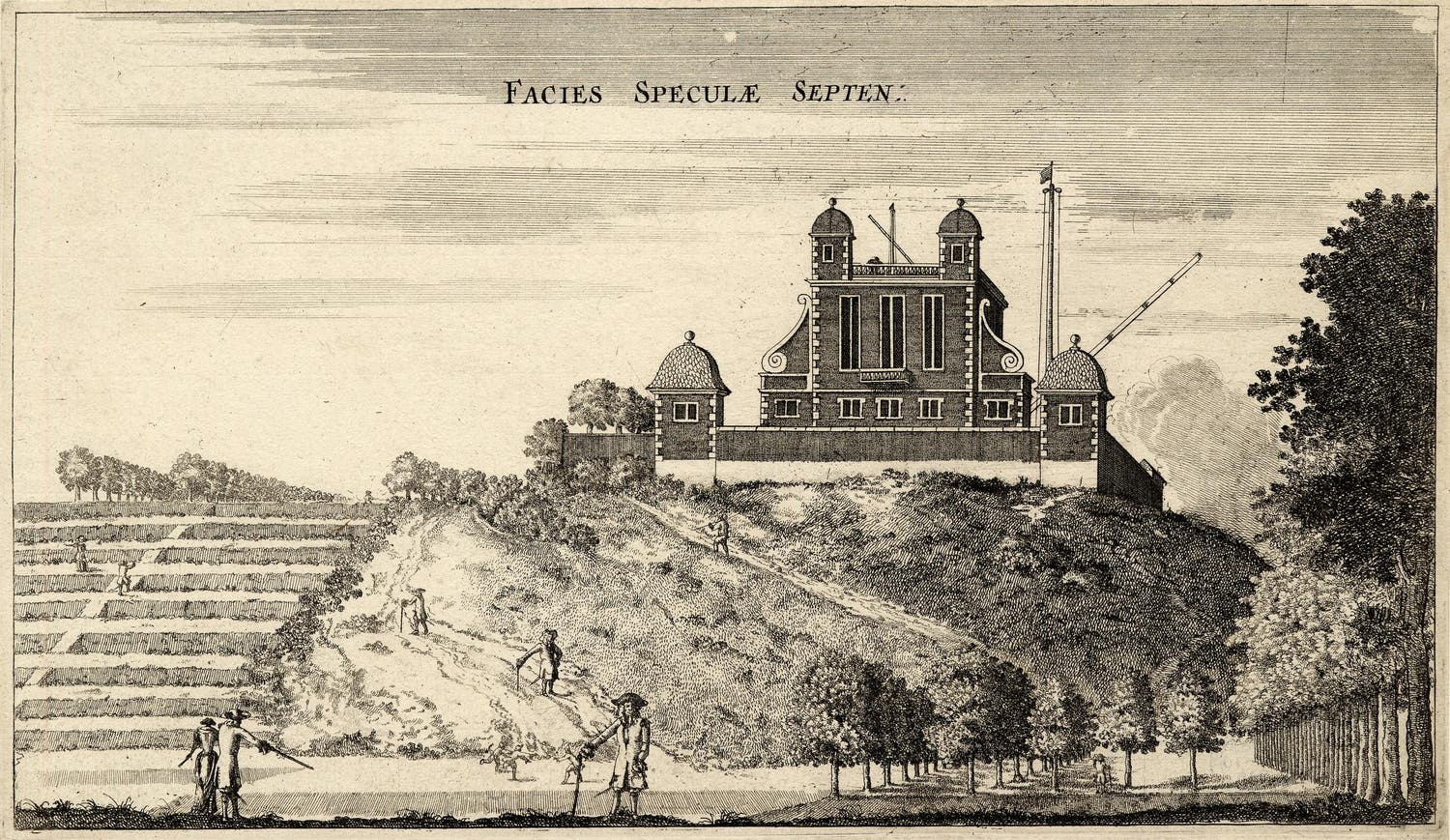

View of Greenwich Observatory from the north. 1676 Etching © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Flamsteed himself set the fire, and expressed joy at watching it. He said that the burned pages were a “sacrifice to truth” - why was he so pleased about a fire that destroyed a not insignificant part of his work? The pages were from the 1712 edition of Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis, which appeared in spite of Flamsteed’s vehement objections. Isaac Newton and Edmund Halley edited the book, which drew upon observations Flamsteed saw as erroneous and obtained under false pretenses. Using their influence and power over Flamsteed and the Observatory and their influence with Queen Anne and her consort Prince George, Newton and Halley caused 400 copies to be printed despite Flamsteed’s protests. About 60 complete copies of the book circulated in 1712, and one of those complete copies was acquired by the Linda Hall Library in 1965. In 1716, Flamsteed partially destroyed the sections of the book he objected to: Halley’s incendiary and unsigned preface, the catalog of the fixed stars, and his observations made with his mural arc. However, with a handful of copies, he set aside the objectionable parts, intending to add his own corrections to the text. In early 2025, the Library acquired one of those copies, joining the complete 1712 edition, the 1725 edition, and his 1729 Atlas Coelestis.

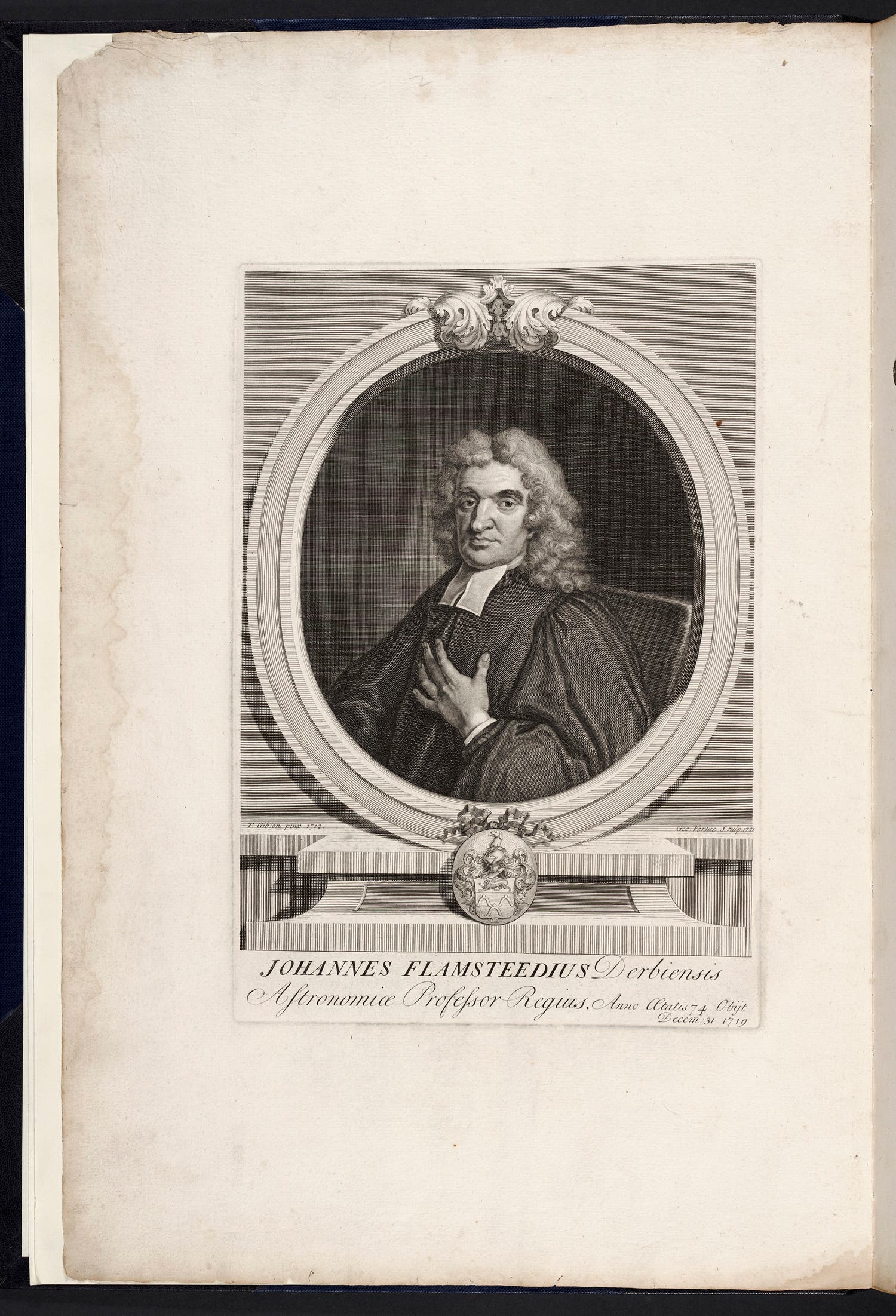

Portrait of John Flamsteed, from the 1729 Atlas Coelestis, Linda Hall Library.

In a letter dated June 2, 1716, Flamsteed writes to one of his colleagues at the Observatory, Abraham Sharp, “I shall take up with me some copys of the corrupte[d] Catalogue etc to be stitcht up for you and some few friends… and I hope to leave one with the Carrier for you directed as you order.”[1] Flamsteed does not state how many copies he “took up,” but of the roughly 60 copies of the 1712 edition that still survive[2], there are four known extant copies that he kept for his friends. The Library’s newly acquired copy is one of those four copies, comprised solely of the sections of the book Flamsteed objected to - specifically, the catalog of the fixed stars, and the observations made with the mural arc[3]. The other known incomplete copies are at the Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum[4], the library of the Royal Astronomical Society[5], and the Greenwich Heritage Centre. These copies are similar, some with the inclusion or exclusion of engraved plates, but generally their contents are the same. The Linda Hall copy is the only one of this group with extensive annotations.

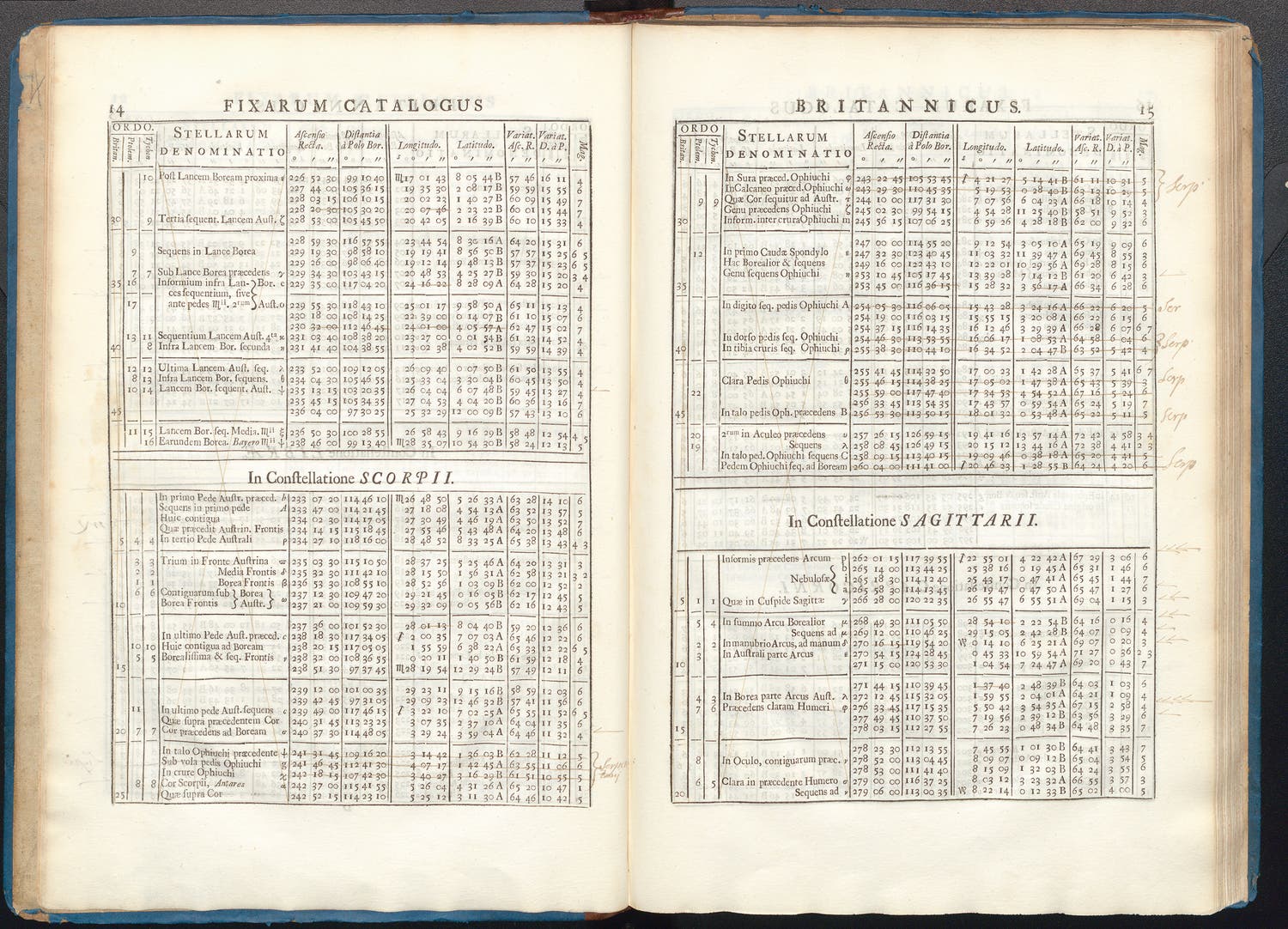

Pages 14 and 15 of Historia Coelestis, with marginal corrections and annotations by Crothswait, Linda Hall Library.

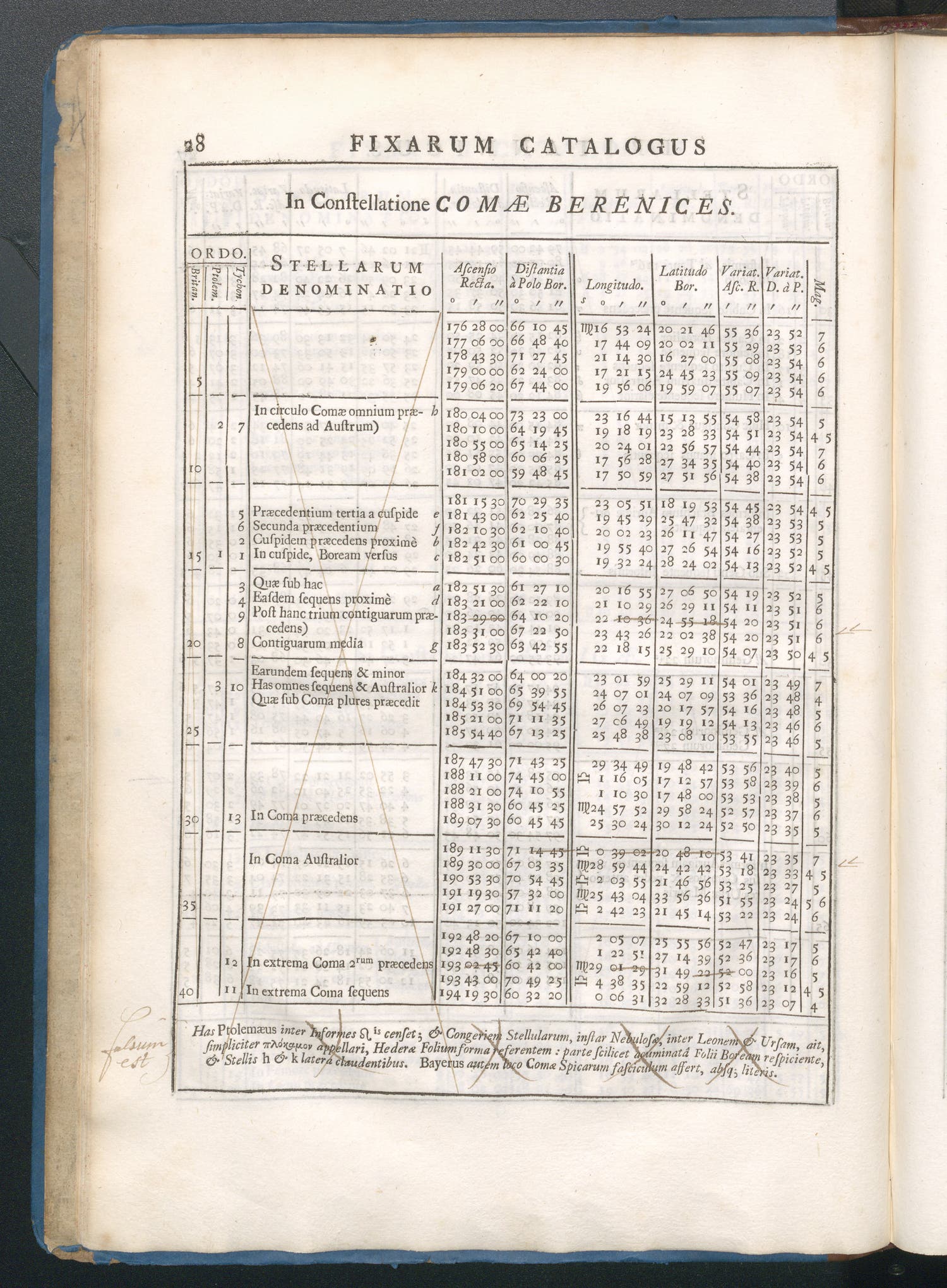

Those annotations are contemporary, only in the first 60 pages of the book, and are in two hands - those of Flamsteed himself, and of his colleague, Joseph Crothswait. The annotations are broadly in four types. Three can be seen on page 28 of the book, in the catalog of the fixed stars in the constellation Coma Berenices.[6]

Page 28 of Historia Coelestis, with annotations by Crothswait, Linda Hall Library.

Annotations, from left to right, begin with the x’s through the columns marked “ORDO Britan.” and “Stellarum Denominatio.” One of Flamsteed’s major objections to the 1712 edition was the addition of numbers for the stars, added by Edmund Halley, and identified by their Britannic (Britan.) number. In every page of the star catalog, this column has been cancelled in the same way. The “Stellarum Denominatio” column receives similar treatment - Flamsteed disagreed with the placements that Halley assigned to all the stars in each constellation, and so each column in the catalog is cancelled.

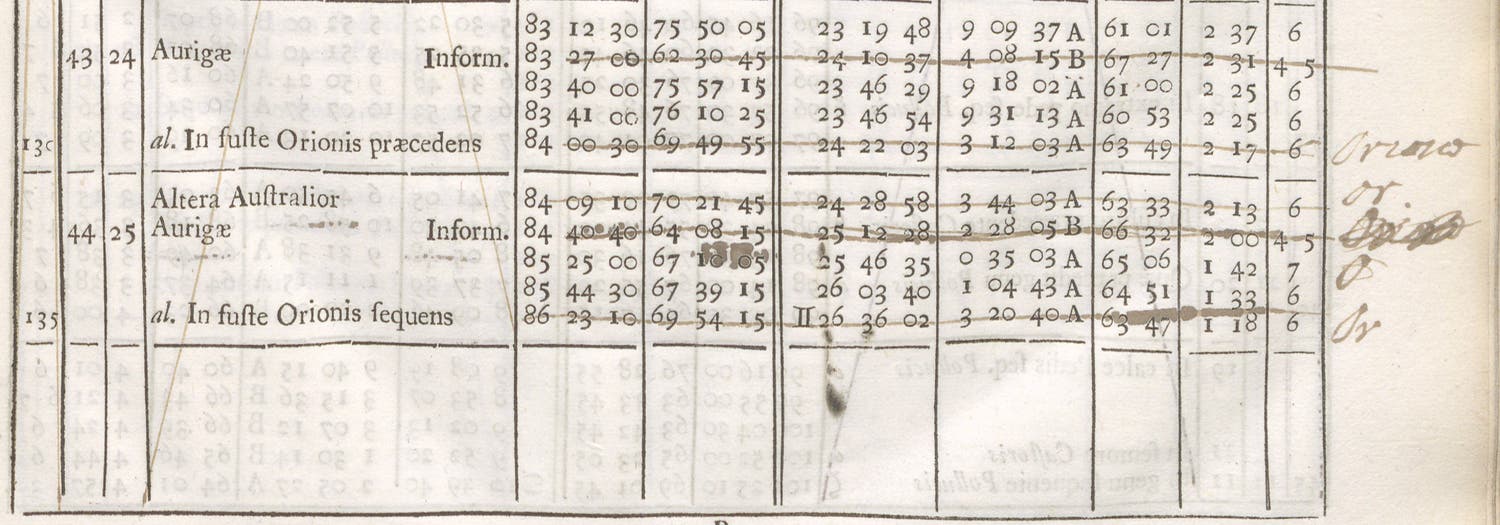

Second among the annotations are the mark-throughs of specific figures. These denote positions and measurements Flamsteed saw as either fabricated by Halley or preliminary figures he was not able to correct to his normal standards. His method of generating these observations and positions involved multiple observations over time, all of which were condensed and corrected mathematically - something that both Abraham Sharp and Joseph Crothswait were employed by Flamsteed to undertake. This reveals one of his other objections to the 1712 edition - that he saw many of the results, especially in the catalog of the fixed stars, as incorrect, preliminary, and shoddily edited by Halley. Strikethroughs of entire rows indicate that Flamsteed saw the entire position as incorrect, though new positions are not provided. Alternatively, if a struck through row has an abbreviation in the margin, this denotes that Flamsteed placed the star in another constellation, as we see in his hand on p. 5, noting the star to be moved to Orion:

Marginal correction in Flamsteed’s hand, on page 5 of Historia Coelestis, Linda Hall Library.

Third, the arrows in the right hand margin indicate the insertion of specific stars from other constellations. In Coma Berenices, Crothswait has added (at Flamsteed’s instruction) two stars into the constellation, which do appear in the 1725 edition of the book, and as such comprised all of the parts of the book as it appeared.

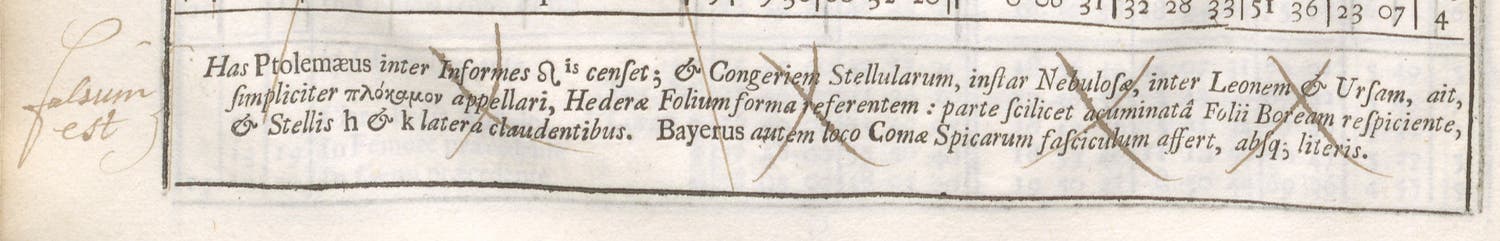

Fourth, and perhaps the strongest correction to the book, is at the base of page 28. The printed note by Halley reads “Has ptolemaeus inter informes [Leonis] censet; et congeriem stellularum, instar nebulosae inter Leonem et Ursam, ait, simpliciter πλόκαμος appelari, Hederae folium forma referentem: parte scilicet acuminata Folii Boream respiciente, et stellis h et k latera claudentibus. Bayerus autem loco Comae Spicarum fasiculum assert, absq; literis.”

Crothswait’s manuscript corrections to Halley’s printed text, page 28 of Historia Coelestis, Linda Hall Library.

[Ptolemy considers these to be among the shapeless Leo; and he says that the cluster of stars, like a nebula between Leo and Ursa, should simply be called [plokamon e.g. locks or braids of hair], referring to the shape of an Ivy leaf: namely, the pointed part of the leaf facing north, and the stars h and k closing the sides. But Bayer asserts that instead of hair there is a bundle of wheat, without letters.] This entire note is struck through, with a marginal note (again, in Crothswait’s hand) that reads “falsum est.” Here, Flamsteed is stating that Halley does not understand Ptolemy and has misread Bayer’s star catalog, which is correct. In his Almagest, Ptolemy describes the stars that now are identified as the Coma Berenices as a cluster of stars, like a nebula, and uses the Greek word for locks of hair for it. Halley is correct here, but his assertion that Bayer (in his Uranometria) identifies the same cluster of stars as wheat is incorrect. While Bayer uses a sheaf of wheat in plate 5, he depicts it as hair in plate 2. Bayer only identifies the stars in plate 2 as the Coma Berenices. In plate 5, he gives an explanation of the history of the identification of the star cluster[7].

These annotations help us to understand the production of this book and who annotated it. Returning to the letter of June 2, Flamsteed says to Sharp that “all the faults are marked in it with lines under them the stars that are false placed are marked in the Margent whe[n] you compare them with my own Catalogue… with it in the same cover are bound up his [e.g. Halley’s] sorry abstracts of the planetary observations taken with my Murall arch…” These descriptions match this copy, and in 1993, Owen Gingerich identified this copy in the sale of the library of Robert S. Dunham (1906-1991). He was underbidder for the lot, but acquired the volume from the successful bidder (Graham Arader), and subsequently published the first examination of the book in an edited volume in 1997[8]. He identified the bulk of the annotations as being in the hand of Joseph Crothswait. Emma-Louise Hill, an independent Flamsteed scholar, identified the first annotations as being in the hand of Flamsteed himself. Hill also corroborated that this is the only known copy of the book with corrections from Flamsteed and his circle. Furthermore, Hill’s work identifying known complete and incomplete copies of the 1712 edition identifies that this is the only copy that matches Flamsteed’s description of the copy he sent to Abraham Sharp, described in the June 2 letter.

The other significant annotated copy of the book resides at the Caird Library, and is the proof copy of Edmund Halley, with his extensive corrections and annotations[9]. It is not solely the parts of the book Flamsteed destroyed, but is an early state of the book.

Our copy of the book is bound in blue paper over boards, with a modern calf spine. It has the binder’s ticket for the Green Dragon Bindery in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, who rebound the book for Gingerich. Recent communication with the bindery reveals that they completed a “full rebind” which preserved the pastedowns. The boards were covered in “blue chart paper” by the bindery, which replaced the “old quarter calf” described in the Dunham sale for the copy. Interestingly, Gingerich speculates that the old paper was similar to other bindings Flamsteed commissioned for the Observatory[10]. However, due to the rebind, the original binding has been lost and so his speculation cannot be fully investigated. Work tracing the volume’s provenance will continue.[11]

Several aspects of the book warrant further study and exploration. The Library’s Jason W. Dean is currently working with Emma-Louise Hill on a multi-essay project exploring existing complete and incomplete copies of the 1712 Historia Coelestis. The project will explore the copies’ survival rate and the bibliographical issues and states for the book. It will also explore how this copy and the three other incomplete copies mentioned above can be used to better understand one of the most engaging conflicts in the early Royal Society, and 18th century science more generally—the conflict between John Flamsteed, Isaac Newton, and Edmund Halley over the publication and destruction of the 1712 Historia Coelestis.

The addition of this unique and significant copy enables Library users to examine it next to a complete copy of the 1712 edition, the 1725 edition, and Flamsteed’s Atlas Coelestis. Three libraries worldwide offer this unique opportunity: the Linda Hall Library, the Caird library, and the library of the Royal Astronomical Society. Users can further explore Flamsteed’s legacy at the Linda Hall Library. The Library’s collection of astronomy includes the 1776 and 1795 French editions of Flamsteed’s work, Bode’s improvements to Flamsteed’s atlases (1782 and 1805), and Caroline and William Herschel’s correction and expansion of Flamsteed’s star catalog, their Catalogue of Stars of 1798.

The book is now available to consult by appointment, and is also fully digitized in the Library’s catalog. It will also be highlighted in the New Acquisitions show at the Library in 2025.

[1] Flamsteed to Sharp, June 2, 1716, in The Correspondence of John Flamsteed, vol. 3, p. 795 (letter no. 1424).

[2] These copies have been identified by Emma-Louise Hill.

[3] Three mural arcs were used by Flamsteed at the Observatory. It was only with the installation of the third one, installed in 1689, that Flamsteed was able to make the observations he desired. He then set about revising the prior mural arc observations, which were not included in the 1712 edition, among his objections.

[4] Caird Library shelfmark PBG0112

[5] Royal Astronomical Society Library shelfmark ACC 954

[6] The fixed stars listed in the catalog are arranged by their locations within constellations, and the catalog provides a number of data points for each star, including its right ascension and declination.

[7] For more information on the Coma Berenices/Bayer identification see the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s Observer’s Handbook 2017, p. 272.

[8] Gingerich, ‘A unique copy of Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis,’ pp. 189-197 in Flamsteed’s Stars: New Perspectives on the Life and Work of the First Astronomer Royal, 1646-1719 (Willmoth, ed.) (1997), p. 189-197.

[9] Caird Library shelfmark PBN1363

[10] Gingerich, 193

[11] Not mentioned in this essay is the bookplate on the front pastedown of William Walker Drake. Investigation into the disposition of this copy after the death of Abraham Sharp is also in progress.