History of Science on Display: Dukedom Large Enough

Twelve years before the action of The Tempest, Prospero, the Duke of Milan, was usurped by his brother Antonio and set adrift on a “rotten carcass of a boat” to die with his infant daughter Miranda. Instead, Prospero and Miranda are shipwrecked on an island where the only other inhabitants are Caliban, a monster, and the benevolent spirit, Ariel.

A kindly Neapolitan, Gonzalo, sends books from Prospero’s library into exile with him.

Knowing I lov’d my books, he furnish’d me

From mine own library with volumes that I prize above my dukedom.

(Prospero, Act I, Scene II)

No longer the Duke of Milan, Prospero finds solace in his books.

My library was dukedom large enough

(Prospero, Act I, Scene II)

Prospero learned the beneficial art of “white” or “natural” magic from his books about nature and uses his powers to manipulate his environment and those around him, the better to protect Miranda, vanquish his opponents, regain the dukedom of Milan, and arrange Miranda’s happy marriage. When his work is complete, he vows to renounce his magic.

This rough magic I here abjure, and, when I have required some heavenly music, which even now I do, To work mine end upon their senses this airy charm is for, I’ll break my staff, Bury it certain fathoms in the earth, And deeper than did ever plummet sound, I’ll drown my book.

(Prospero, Act V, Scene I)

This exhibition suggests selected titles that might have been in Prospero’s library, had he not been a creation of Shakespeare’s imagination.

Lisa M. Browar

Items featured in this exhibition:

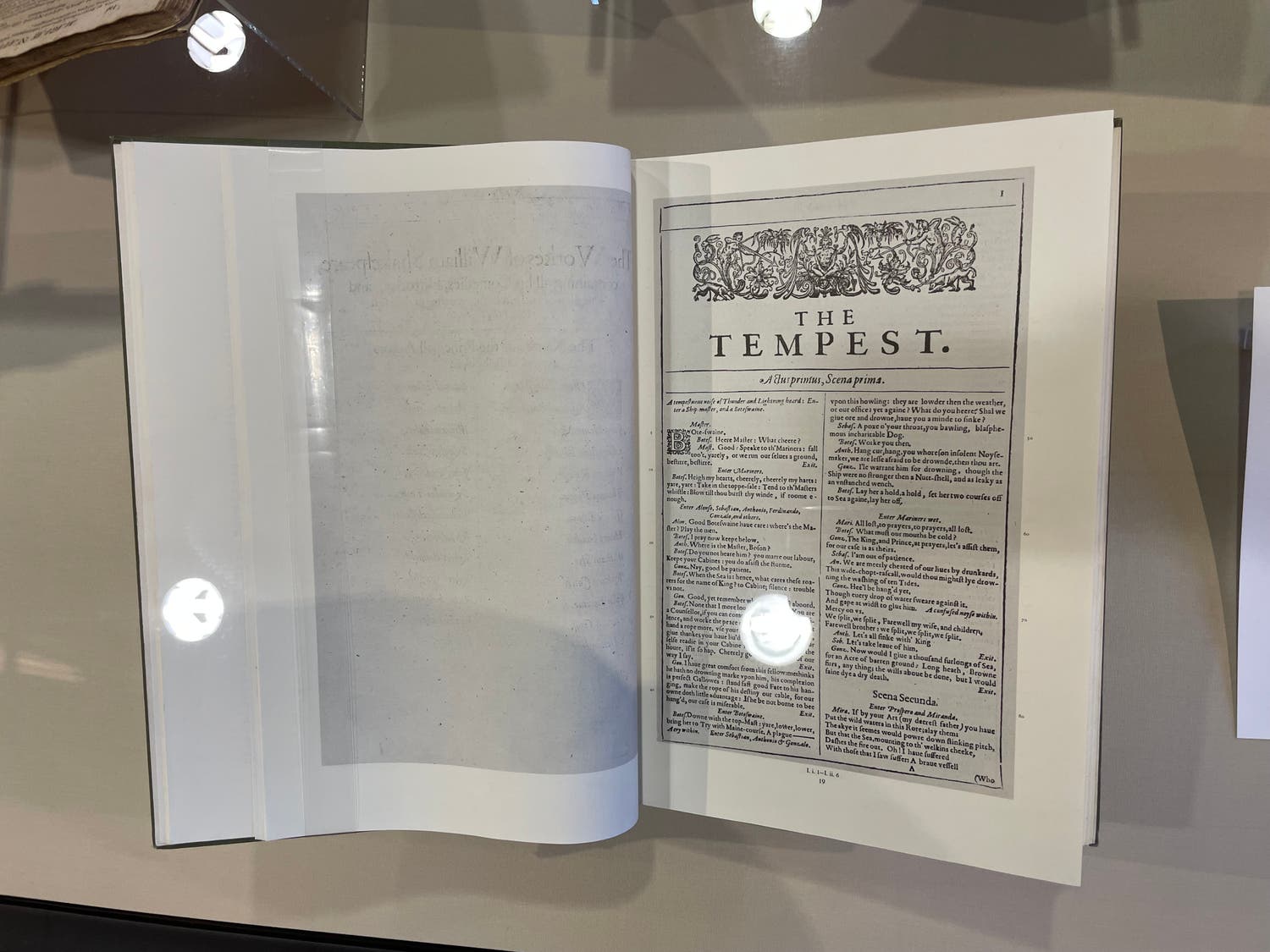

William Shakespeare

The first folio of Shakespeare, prepared by Charlton Hinman

New York, 1968

Gift of David Levy

William Shakespeare, The first folio of Shakespeare, prepared by Charlton Hinman, New York, 1968. Gift of David Levy.

Written between 1610 and 1611, The Tempest is generally held to be Shakespeare’s last independently written play. Although listed in the First Folio as a comedy, the play deals with both tragic and comic themes and for this reason, modern criticism has more recently categorized The Tempest as a romance.

The Tempest is a suggestive play, intimating the late in life concerns of the playwright himself. Shakespeare’s ripest thoughts about life inform certain of Prospero’s speeches and offer a summing up of the playwright’s life upon the stage and the wisdom he accumulated regarding the human condition.

The play’s best-known lines constitute one of the most beautiful expressions of the evanescence of earthly things and offer an eloquent farewell to the theater.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors As I foretold you, were all spirits, and Are melted into Air Into thin air and like the Baseless fabric of this vision, The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces, The solemn temples, the great globe itself, Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve And, like this insubstantial pageant faded, leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff As dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.

Prospero, Act IV, Scene I

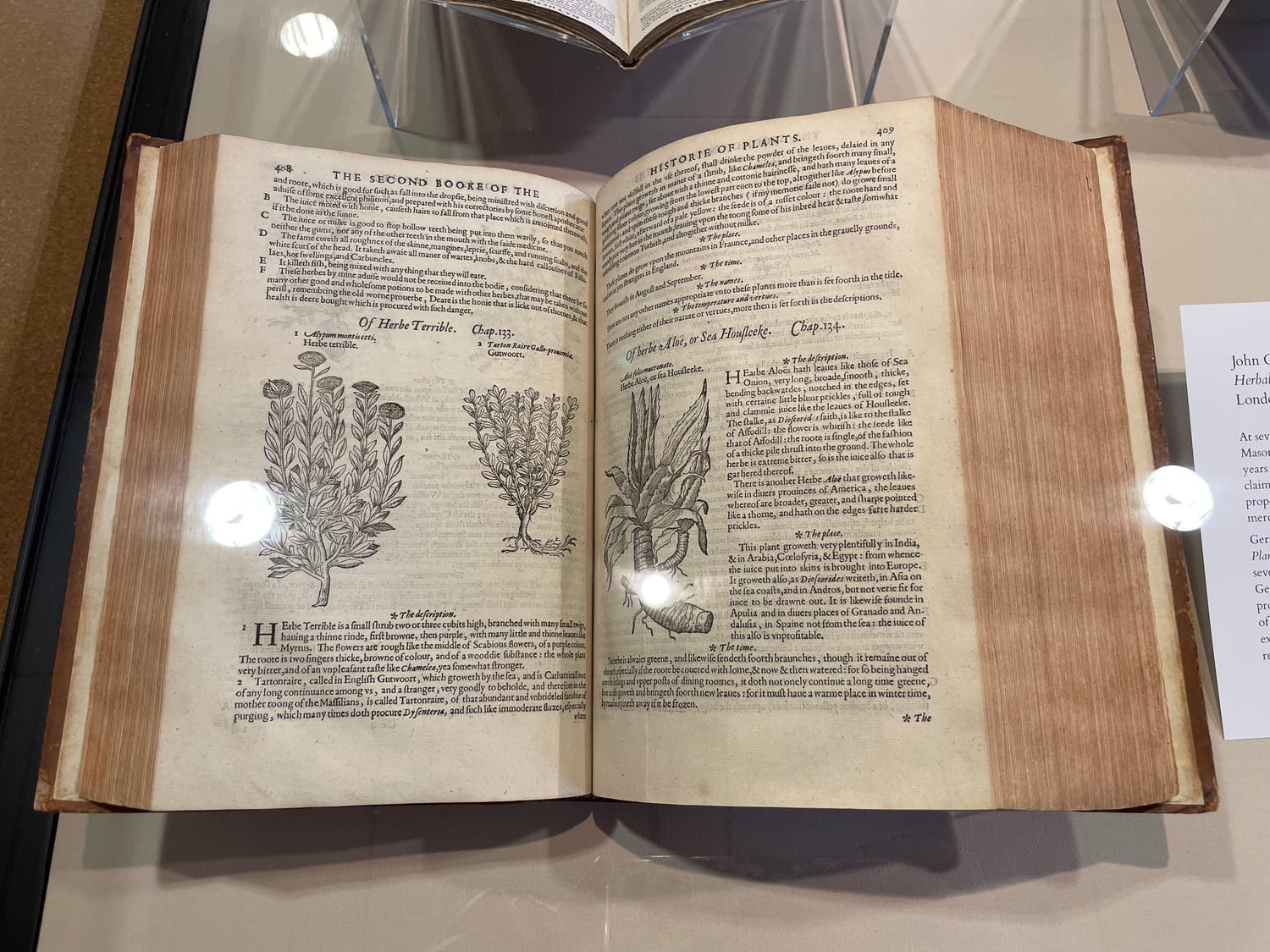

John Gerard

Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes

London, 1597

John Gerard, Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, London, 1597.

At seventeen, John Gerard was apprenticed to Alexander Mason, a barber-surgeon with a large surgical practice. Seven years later, Gerard opened his open surgical practice, claiming to have learned much about plants and their healing properties during his travels abroad as a ship’s surgeon on a merchant ship.

Gerard’s 1,484-page illustrated Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, became a popular gardening and herbal book in the seventeeth century. Published amidst charges of plagiarism, Gerard’s Herball nevertheless included over 1,000 plants and provided readers with the names, habits, and uses (“vertues”) of many plants both known and rare. It was the most exhaustive work of its kind and was considered a standard reference work in its time.

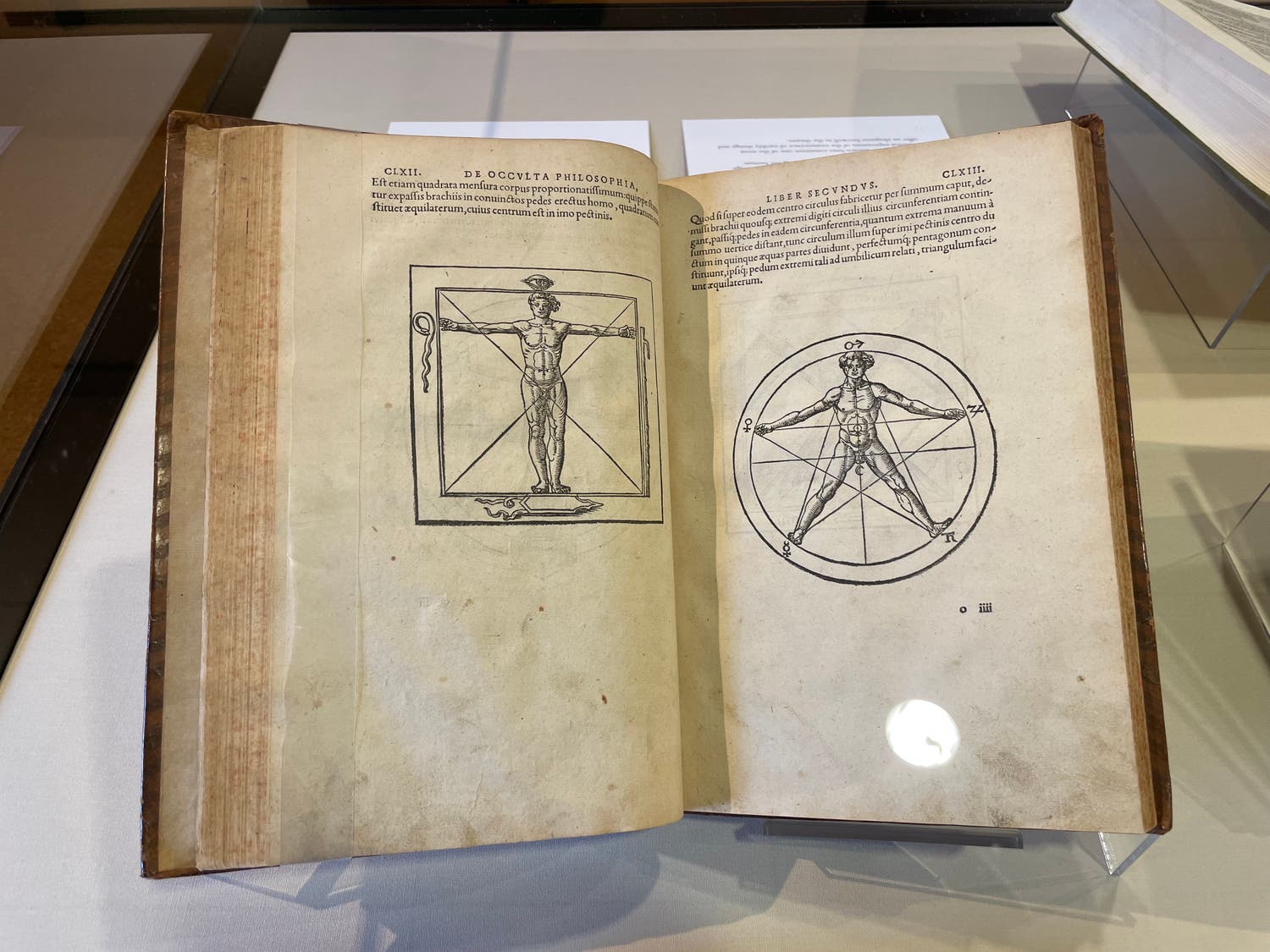

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

De occulta philosophia libri tres

[Three Books Concerning Occult Philosophy]

Paris and London, 1531, 1533

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, De occulta philosophia libri tres, [Three Books Concerning Occult Philosophy], Paris and London, 1531, 1533.

Agrippa was a German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, and occult writer whose Three Books Concerning Occult Philosophy was widely influential among occultists of the early modern period. Agrippa’s most important work, Three Books, argued for a synthetic vision of magic whereby the natural world combined with the celestial and the divine.

Giovanni Giambattista della Porta

Magiae Naturalis

[Natural Magic]

Naples, 1589

Giovanni Giambattista della Porta, Magiae Naturalis, [Natural Magic], Naples, 1589.

Giovanni Giambattista della Porta was an Italian scholar, polymath, and playwright who lived in Naples at the time of the Renaissance, Scientific Revolution, and the Reformation. He spent most of his life pursuing scientific endeavors, benefitting from tutors and visits from renowned scholars.

Magiae Naturalis is a work of popular science covering a variety of subjects investigated by the author including occult philosophy, astrology, alchemy, mathematics, meteorology, and natural philosophy. First published in Naples in 1558, the work’s popularity ensured its republication in five Latin editions within ten years with translations into Italian, French, Dutch, and English.

This book is an example of pre-Baconian science. Its sources include the ancient learning of Pliny the Elder and Theophrastus, as well as scientific observations made by the author.

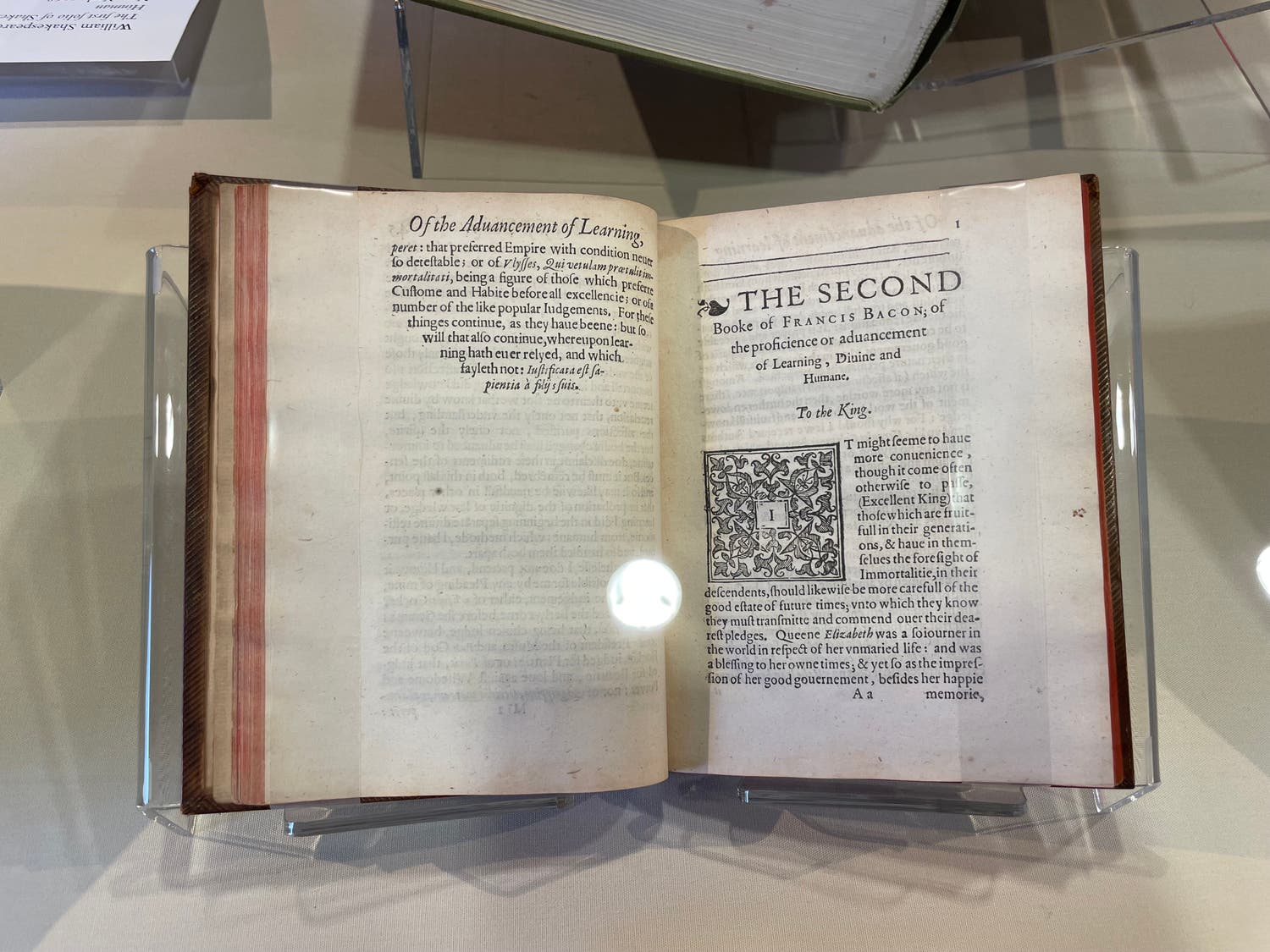

Francis Bacon

The Two Bookes of Francis Bacon

London, 1605

Francis Bacon, The Two Bookes of Francis Bacon, London, 1605

Sir Francis Bacon was an English philosopher and statesman whose works contributed to the scientific method and remained influential through the later stages of the scientific revolution.

Bacon is famous for his role in the scientific revolution, begun during the Middle Ages, promoting scientific experimentation as a way of glorifying God and fulfilling scripture. He has been called the father of empiricism, arguing for the possibility of scientific knowledge based only upon inductive reasoning and careful observation of events in nature.

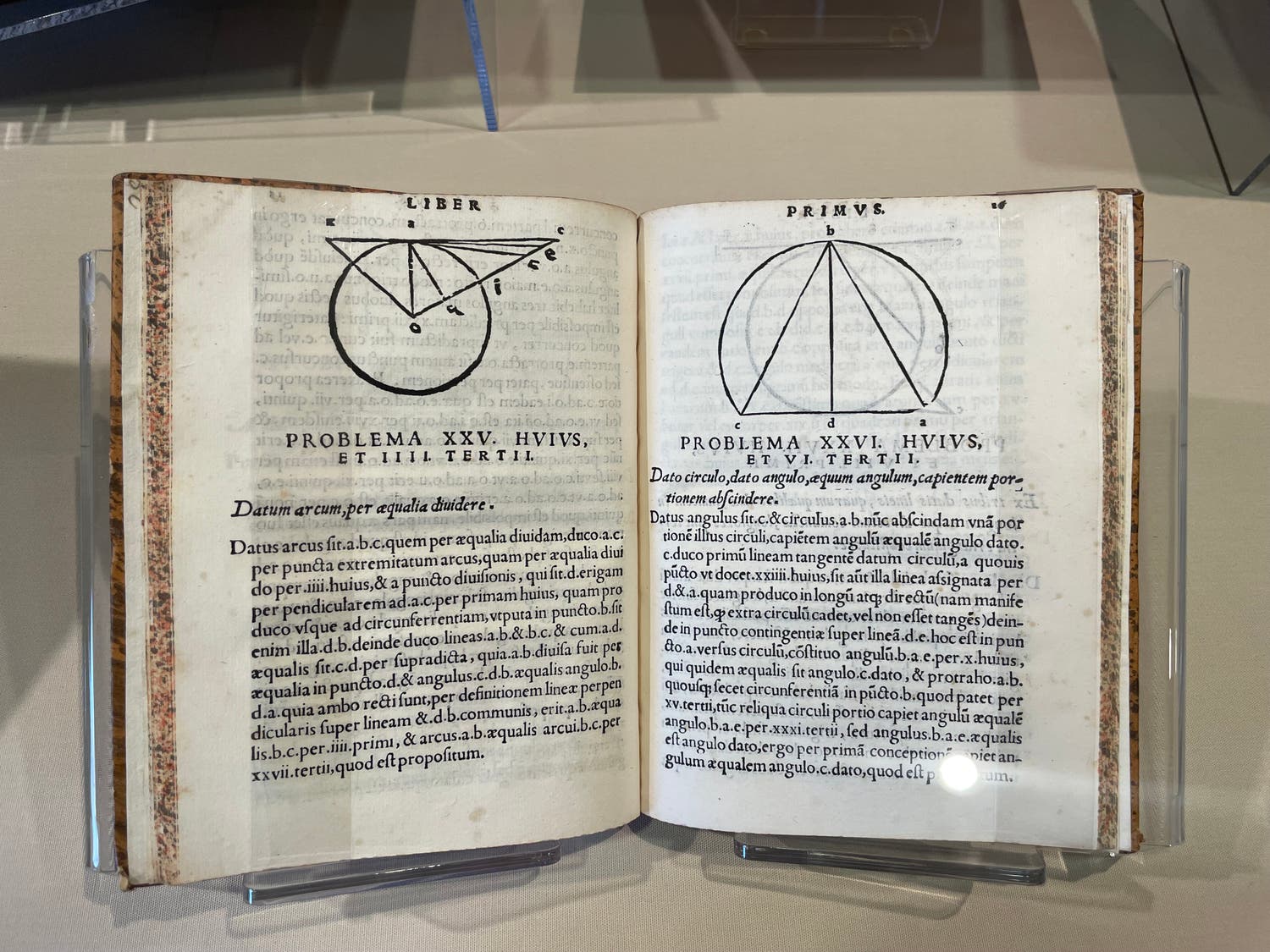

Giambattista Benedetti

Resolutio omnium Euclidis problematum

Venice, 1553

Giambattista Benedetti, Resolutio omnium Euclidis problematum, Venice, 1553.

Giambattista Benedetti was a Venetian mathematician who was also interested in physics, mechanics, the construction of sundials, and the science of music.

In Resolutio omnium Euclidis problematum Benedetti proposed a new doctrine of the speed of bodies in free fall. The accepted Aristotelian doctrine at the time was that the speed of a freely falling body is directly proportional to the total weight of the body and inversely proportional to the density of the medium. Benedetti’s view was that the speed depends on just the difference between the specific gravity of the body and that of the medium. His theory predicts that two objects of the same material but of different weights would fall at the same speed, and that objects of different materials in a vacuum would fall at different though finite speeds.

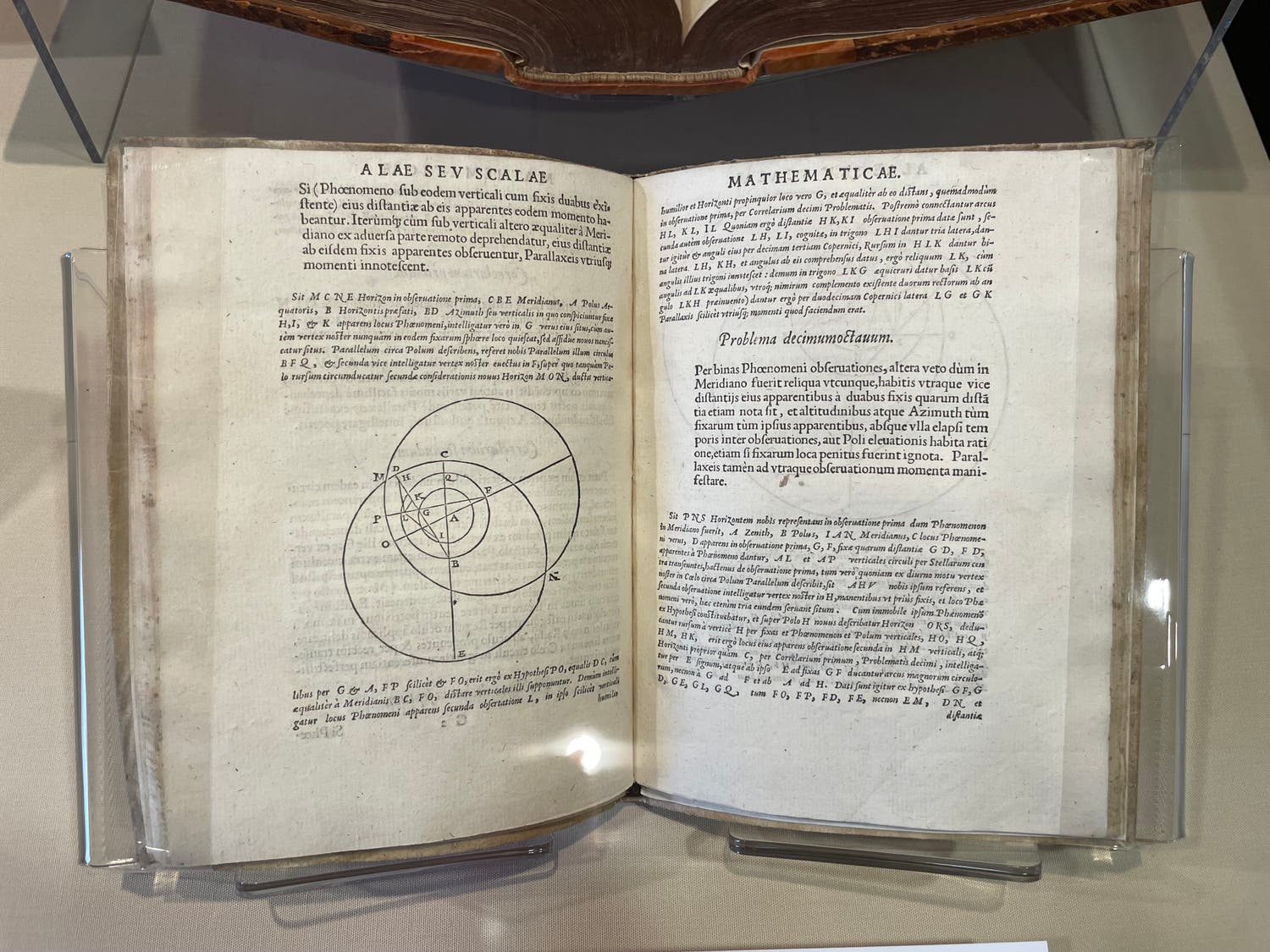

Thomas Digges

Alae seu scalae mathematicae…

London, 1573

Thomas Digges, Alae seu scalae mathematicae…, London, 1573.

The son of mathematician Leonard Digges, Thomas Digges grew up under the guardianship of John Dee, the Renaissance natural philosopher following Leonard’s death. In 1576, Digges published a new edition of his father’s perpetual almanac, A Prognostication everlasting, adding new material in several appendices. The most important of these was A Perfit Description of the Caelestiall Orbes according to the most aunciente doctrine of the Pythagoreans, latelye revived by Copernicus and by Geometricall Demonstrations approved. This appendix featured a detailed discussion of the controversial and at the time poorly known Copernican heliocentric model of the Universe. This was the first publication of that model in English, and a milestone in the popularization of science.

Tycho Brahe

Astronomiae instauratae progymnasmata

[Introduction to the New Astronomy]

Prague, 1602

![Photo of a book by Tycho Brahe, Astronomiae instauratae progymnasmata [Introduction to the New Astronomy]](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/f5c910e1-c55a-4935-95ac-d96d0cc40e79/8.0_Brahe_Astronomiae.JPG?w=1500&h=1125&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Tycho Brahe, Astronomiae instauratae progymnasmata, [Introduction to the New Astronomy], Prague, 1602.

Tycho Brahe was a Danish astronomer known for his accurate and comprehensive astronomical observations. In his lifetime, Tyco was well known as an astronomer, astrologer, and alchemist, and was described as “the first competent mind in modern astronomy to feel ardently the passion for exact empirical facts.

The two volumes of Astronomiae instauratae progymnasmata contain Brahe’s theories about the motion of the sun, comet observations, and an account of Tycho’s system of the world.

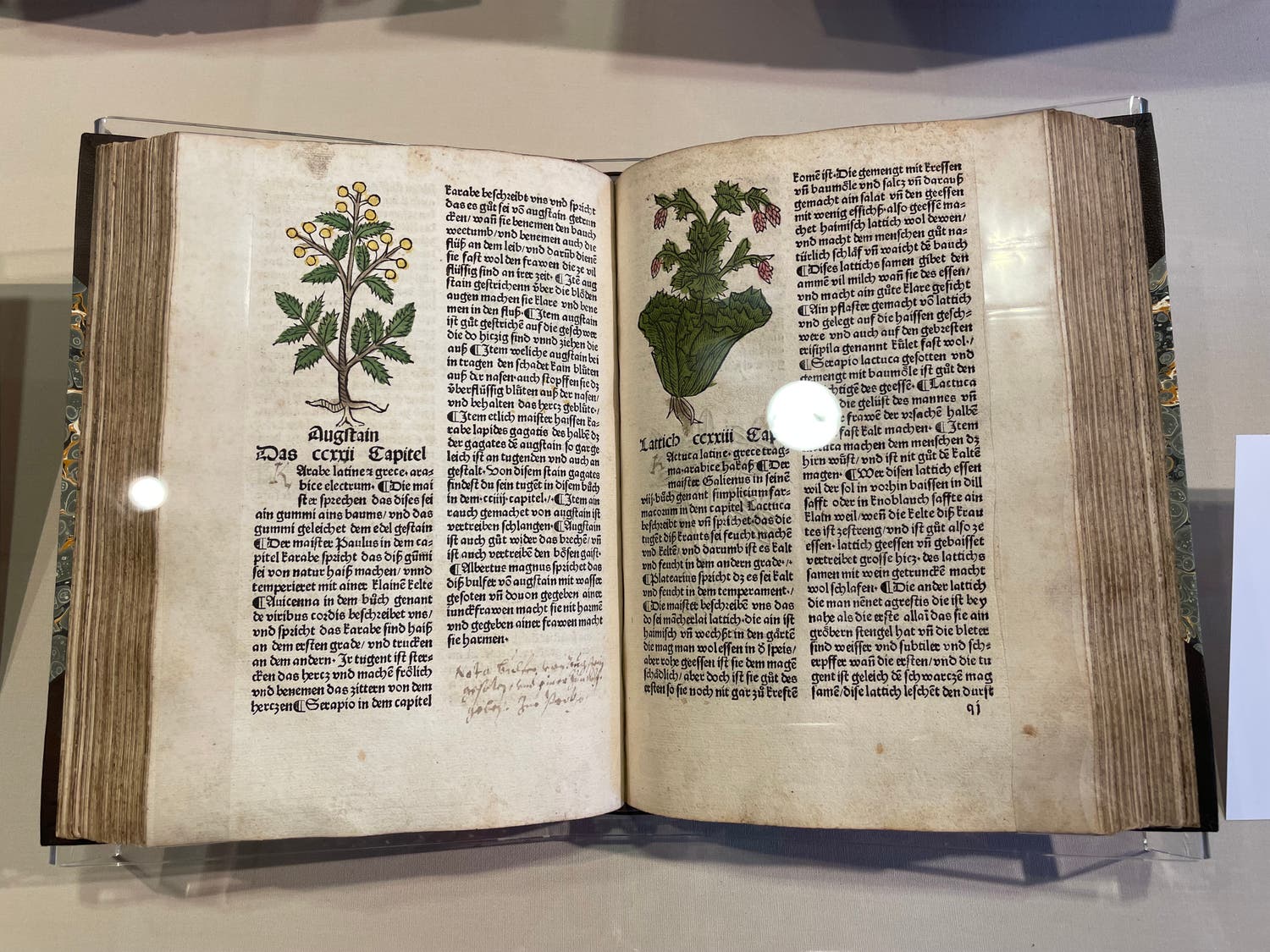

Ain Garten der Gesundheit

[Garden of Health]

Ulm, 1487

Ain Garten der Gesundheit, [Garden of Health], Ulm, 1487

One of the first printed herbals in German, Gart der Gesundheit is an important late medieval work concerning the knowledge of natural history, especially that of medicinal plants. In 435 chapters, 382 plants, 25 drugs from the animal kingdom, and 28 minerals are described and illustrated. The text is a collection of earlier texts in German and in Latin on drugs from the herbal, animal, and mineral kingdoms.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Forbidden Planet

1956

Loan from private collection

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Forbidden Planet, 1956. Loan from private collection.

Forbidden Planet is a 1956 American science fiction film based on an original film story by Allen Adler and Irving Block. The characters and isolated setting have been compared to those in William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the plot contains analogues to the play leading many to consider it a loose adaptation. Today, Forbidden Planet is considered a science fiction classic.

The characters of Dr. Morbius, Altaira, and Robby the Robot, strongly suggest The Tempest’s Prospero, Miranda, and Ariel; the conceits of shipwreck, exile, rescue, and return to civilization are similarly derived from Shakespeare’s play.

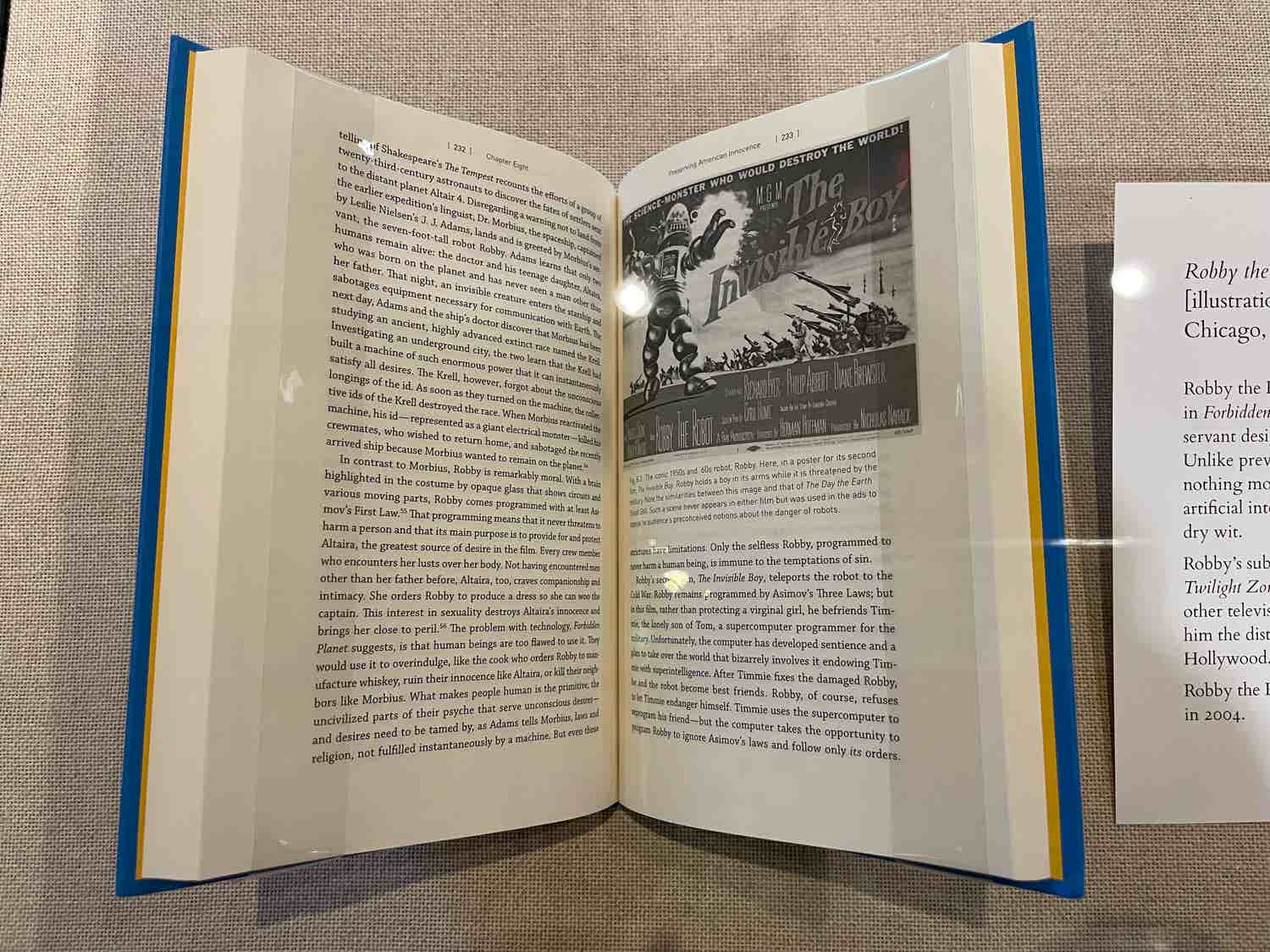

Robby the Robot

[illustration from American Robot]

Chicago, 2020

Robby the Robot, [illustration from American Robot], Chicago, 2020.

Robby the Robot is a science fiction icon who first appeared in Forbidden Planet. In the film, Robby is a mechanical servant designed, built, and programmed by Dr. Morbius. Unlike previous movie robots who were required to be nothing more than menacing in appearance, Robby exhibits artificial intelligence along with a distinct personality and a dry wit.

Robby’s subsequent popularity led to roles in episodes of The Twilight Zone, Lost in Space, The Man from U.N.C.L.E and other television shows, commercials, and movies, earning him the distinction as “the hardest working robot in Hollywood.”

Robby the Robot was inducted into the Robot Hall of Fame in 2004.

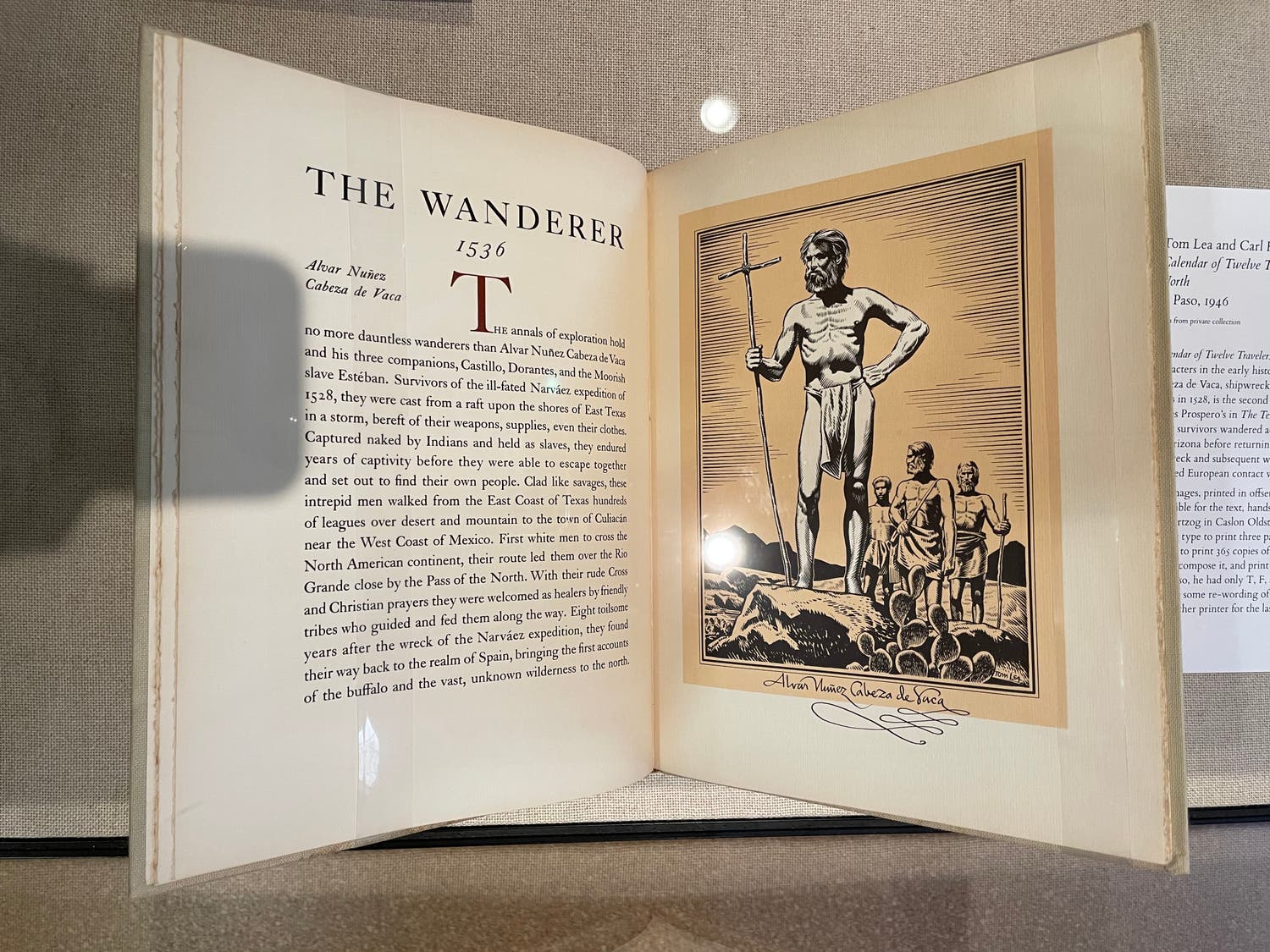

Tom Lea and Carl Hertzog

Calendar of Twelve Travelers Through the Pass of the North

El Paso, 1946

Loan from private collection

Tom Lea and Carl Hertzog, Calendar of Twelve Travelers Through the Pass of the North, El Paso, 1946. Loan from private collection.

Calendar of Twelve Travelers sketches twelve significant characters in the early history of El Paso. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, shipwrecked on a small island off the coast of Texas in 1528, is the second person featured. His shipwreck echoes Prospero’s in The Tempest. Cabeza de Vaca and four fellow survivors wandered across today’s Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona before returning to Mexico in 1532. The shipwreck and subsequent wanderings represented the first extended European contact with the native peoples of Texas.

Lea’s images, printed in offset, are striking. He was also responsible for the text, handset and letterpress printed by Carl Hertzog in Caslon Oldstyle. Hertzog only had enough standing type to print three pages at a time, and required Hertzog to print 365 copies of those three pages, break up the type, re-compose it, and print 365 copies of the next three pages. Also, he had only T, F, and W as the initial letters, requiring some re-wording of the text. The A was borrowed from another printer for the last entry.

The Linda Hall Library holds one of the best collections of rare printed science, technology, and engineering works in the world. Each month, our History of Science experts will curate a special collection of rare books for Library visitors to enjoy. The current display, Dukedom Large Enough, will be on display in the Library’s West Exhibit Hall through December 2022.

The Library is open to the public free of charge during regular Library hours, Monday – Friday, 10:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.