Gardens of Knowledge: Cultivating Science and Information in Early Modern Horticulture Books

Cropping up throughout the Linda Hall Library’s holdings is a substantial collection of early modern European horticultural and agricultural texts. While these books about cultivating plants span several centuries and many geographical regions, the collection is especially strong in eighteenth century English texts. These books reflect a broader interest in not only the production of food and beautification of land, but also exploration, innovation, and experimentation in several arts and sciences. The production of manuals, botanical observations, explicit descriptions of natural “experiments,” and expensive dictionaries and encyclopedias contributed to the expansion and encouragement of natural sciences, particularly when aligned with the domestic economy and household information.

Books on horticulture, small-scale plant cultivation, and agriculture, large-scale farming, have been written for thousands of years. Given the fundamental importance of food cultivation throughout various cultures and eras, it is natural that authors have been drawn to this subject. Medieval husbandry guides served as a noteworthy precursor to early modern horticultural texts, offering a wealth of information for managing rural estates, encompassing activities such as gardening, large-scale crop management, beekeeping, masonry, cleaning, culinary recipes, and more. They served both practical and aspirational purposes, providing readers with guidance on creating an upright and self-sufficient home suitable for a morally upright homeowner. In essence, they presented an ideal estate for ideal families.

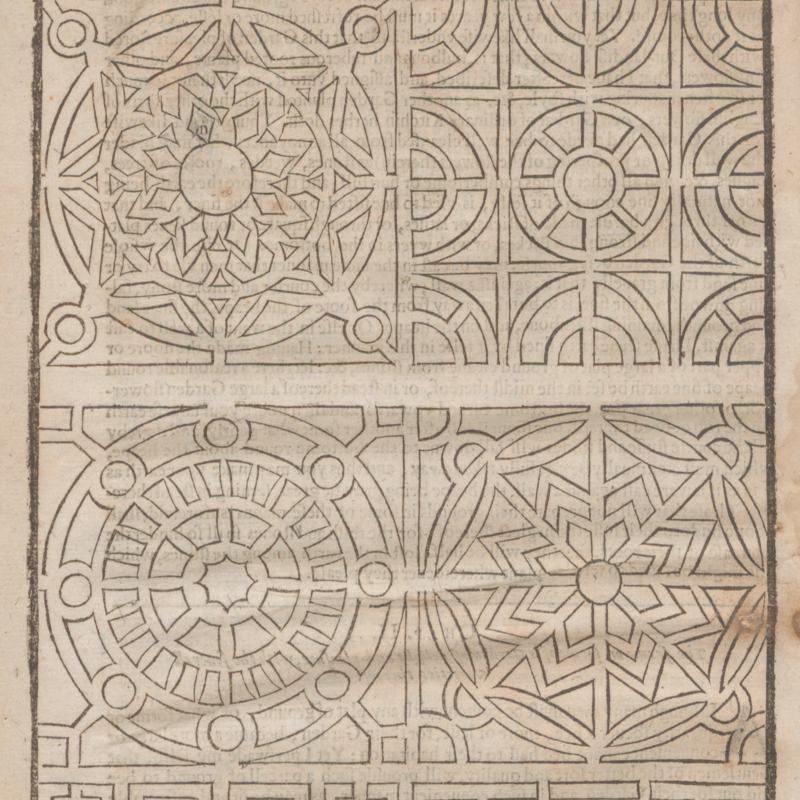

Patterns for use in garden design found in John Parkinson’s Paradisi in sole paradisus terrestris, 1635.

Medieval and early modern herbals concurrently presented another form of horticultural text. Herbals contained descriptions and uses of plants and usually contained many illustrations, notably of varying degrees of accuracy. The texts presented practical information about identifying, cultivating, and preparing plants for medical and culinary uses, serving as important references for medical professionals and households alike.

John Parkinson’s Paradisi in sole paradisus terrestris, first printed in 1629, marks a shift in English horticultural literature. While this text by Parkinson, the Apothecary of London, retains information found in herbals, it also includes separate sections on flower and kitchen gardens and orchards, patterns for garden design, and recipes incorporated into the “uses” of individual plant descriptions. The book is an all-purpose guide for a discerning reader, on the cultivation, use, and pleasure of plants and gardens.

| By the mid-1600s, the genre of horticultural and agricultural texts was beginning to reflect a heavy influence of more formalized scientific practices in Europe and the rise of natural philosophy and experimentation. Authors tend to focus on botanical descriptions, observations on growth cycles, and suggestions for improving cultivation, including garden design, fertilization, and grafting. One such example is John Evelyn’s Sylva, or, A discourse of forest-trees, and the propagation of timber in His Majesties dominions (1664). Many of these books, like Evelyn’s Sylva, also exhibit a strong connection with major scientific societies, such as the Royal Society of London. In its earliest years, the Royal Society was extremely interested in any kind of botanical, medicinal, or culinary information about plants. |  Title page of John Evelyn’s Sylva, 1664. |

Their journal, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, regularly published letters detailing experiments and observations about these topics. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, Royal Society members were publishing horticultural books featuring a range of topics such as natural experiments, recipes, and gardening calendars.

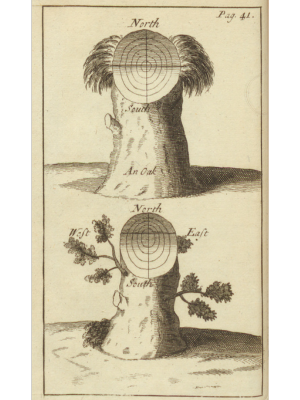

Pierre le Lorrain observes the patterns of ring growth in trees in relation to ordinal direction in Curiosities of nature and art in husbandry and gardening, 1707. | The first half of the eighteenth century witnessed a substantial uptick in publications about gardens, botany, and wide-scale agriculture. Furthermore, these topics were more frequently published independently, rather than incorporated into books containing many related topics, such as husbandry guides. Some of these texts still retained close ties to the Royal Society, like Stephen Hales’s Vegetable Staticks (1727) which heavily relies on previous experiments and observations published in the Philosophical Transactions to execute his experiments on trees. Other texts, like Pierre Le Lorrain’s Curiosities of nature and art in husbandry and gardening (1707), were similarly filled with experiments and observations, but were not explicitly published by or connected to scientific societies. |

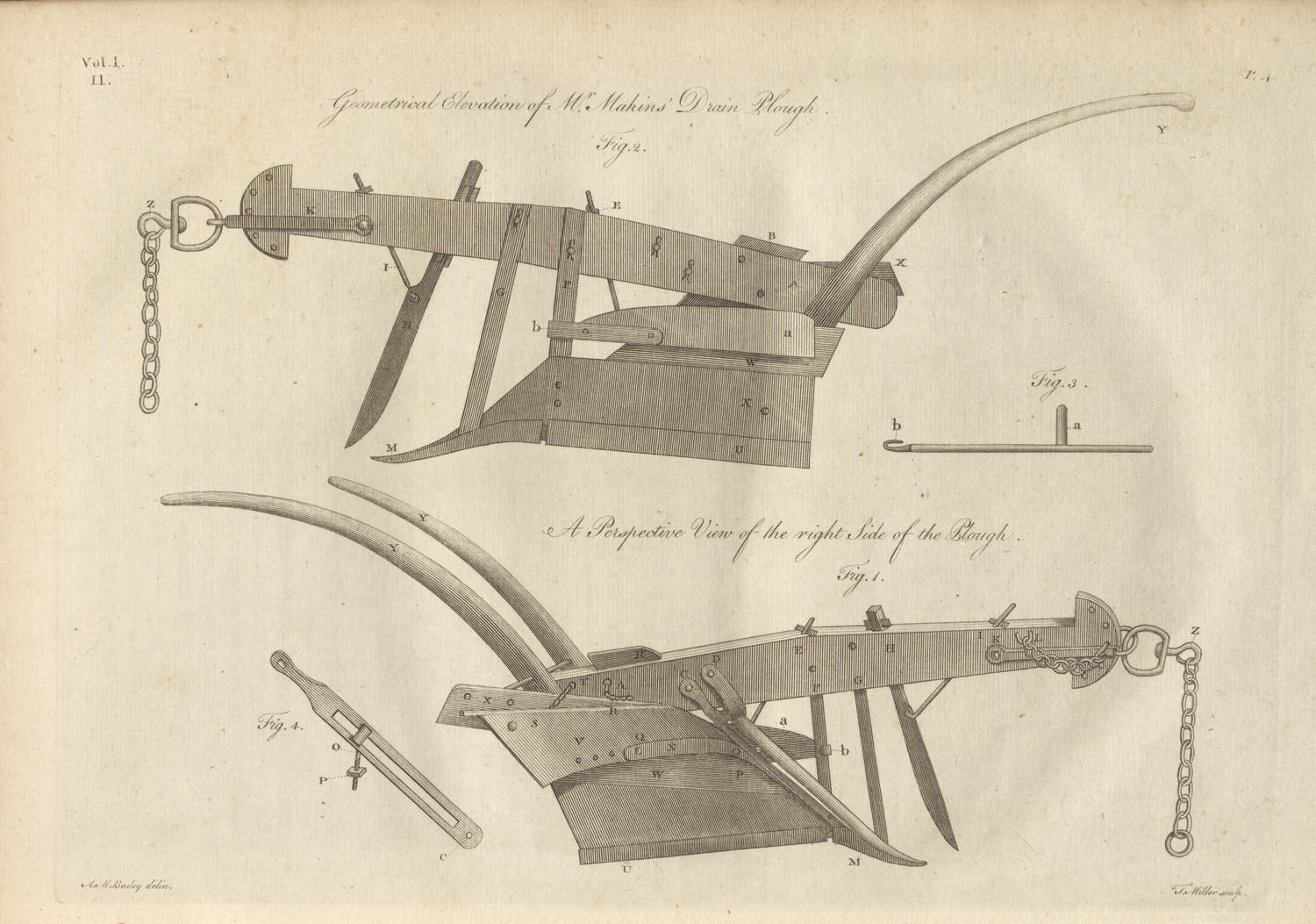

While the establishment of formal gardens was a matter of great consequence to European nobility because of the status and wealth reflected in such cultivation, large-scale agriculture remained a more widespread concern throughout Europe in the eighteenth century. Landholders were interested in more efficient methods of growing crops, while others strove to become landholders, gentlemen farmers, and plantation owners in newlyestablished colonies around the globe. Some books advertised the latest agricultural technologies, like William Bailey’s One hundred and six copper plates of mechanical machines, and implements of husbandry (1782), while others provided instruction in collecting foreign seed and plant specimens for study and cultivation at home, like John Ellis’s Directions for bringing over seeds and plants, from the East Indies and other distant countries, in a state of vegetation (1770).

William Bailey showcases the best agricultural equipment, like this engraving of a drain plow, in One hundred and six copper plates of mechanical machines, and implements of husbandry, 1782.

These veins of publication led to a variety of distinct categories of horticultural books by the late-eighteenth century: large-scale agricultural guides, botanical descriptions, quotidian gardening manuals, and lavishlyillustrated garden designs. Horticultural books had become coveted and practical items in this period for consumers in many social classes. As such, the books were printed in a range of qualities. Some were thin, pocket-sized volumes consisting exclusively of text, or with rudimentary charts and diagrams that could be easily printed. Other books reflected a gentry or noble audience through their generous yet manageable size, thick and durable paper, and the inclusion of detailed charts and engraved images. And finally, a category of horticultural works focused exclusively on the most elite consumers, featuring oversized books with many fine engravings. This category lent itself particularly well to garden design layouts, renderings of architectural elements within garden settings, and giant encyclopedias and dictionaries of horticultural knowledge.

Such a medley of gardening and agriculture books may seem an odd fit for a History of Science collection today, or for the consideration of cutting-edge scientists centuries ago. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, however, regarded the cultivation, use, and discovery of plants as a natural, or scientific, endeavor. Every aspect of a plant, from its growth and uses, was considered through the lens of science. Since the relationship between diet and health had been established for thousands of years, a garden which could produce a household’s fruit, vegetables, and herbs for a year was a serious matter. Furthermore, the herbs produced in a household garden or foraged nearby were regularly transformed into medicinal lozenges, syrups, poultices, and ointments to heal families and communities. A carefully designed garden could improve health, through the bodily experience of natural beauty and fresh air. And understanding and improving the production of crops for entire populations could improve the natural condition of millions of people.

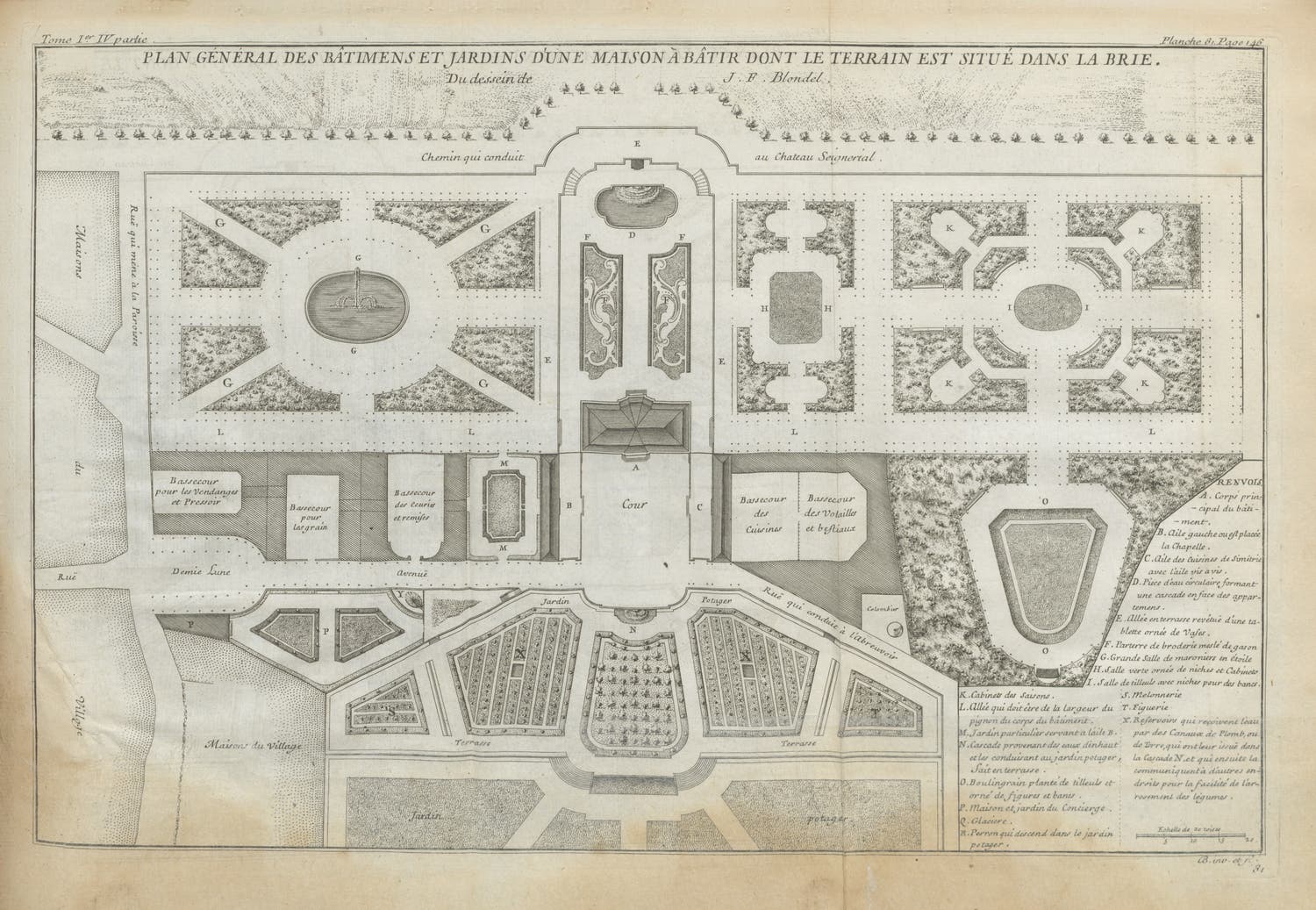

Jacques-François Blondel’s De la distribution des maisons de plaisance, et de la decoration des edifices en general, 1737-38, was printed exclusively for elite consumers. It is lavishly illustrated with renderings of pleasure houses and gardens for the French aristocracy.

Even beyond these issues tied to health, the domestic scientific observation and experimentation encouraged within these books served to expand and promote the sciences to wider audiences and strengthen the role of natural philosophy and science in the broader culture. Because of this relationship centuries ago between gardens and scientific knowledge, horticultural books frequently presented information in a scientific manner. Just as in the literature of other natural sciences of the period, horticultural books provided clear descriptions, diagrams with labels, charts and tables, lists of like information within categories, and explanations of observational conditions and experimental processes. This convergence of gardens and knowledge so many centuries ago is just as relevant in Linda Hall Library’s collections today.