Scientist of the Day - William Samuel Henson

Wlliam Samuel Henson, a British inventor and engineer, was born on May 3, 1812, in Nottingham. Henson was one of the lesser-known aeronautic pioneers who designed heavier-than-air craft before the Wright brothers. Everyone seems to agree that George Cayley was the father of British aeronautics, if not of all aeronautics; in 1810, he laid out exactly what engineers had to do in order to build a powered aircraft. He did not do so himself, because in 1810, steam engines were far too heavy to allow an airplane using one to get off the ground. But Cayley had figured out how to master the problems of lift, control, take-off, and landing.

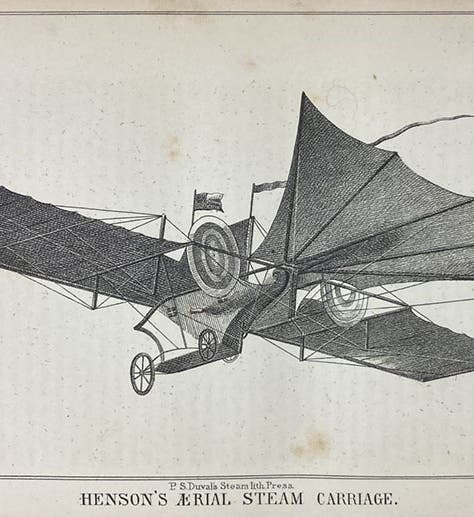

By the time of Henson, who started out as a lace-making engineer, steam engines were a lot lighter. Working in Chard, in Somerset, with fellow lace-maker John Stringfellow, Henson in 1841 built a lighter steam engine, and in 1842 he designed a large airplane, powered by that engine, which he and Stringfellow patented in 1843. The aircraft had a wingspan of 150 feet and was intended to carry passengers. The large single wing had cambered struts covered by fabric, and there was a tail with a rudder for control. The only thing lacking were ailerons to provide for lateral control, which was curious, since Henson apparently had read Cayley's papers, and Cayley had emphasized the vital importance of lateral control.

In 1843, Henson, Stringfellow, and two others formed a company, the Aerial Transit Company, to build and market their monoplane. They must have had a good business manager (I think Frederick Marriott filled that function), for they commissioned all sorts of prints of their proposed plane, which they called "Ariel," or the "Aerial Steam Carriage” (third and fourth images). One of the prints showed Ariel flying over Egypt, with the pyramids in the background. Henson also published a booklet of “Specifications," as he called it, which contained colored schematics of his proposed craft, with which to entice investors. Copies are scarce today, but there is one in the possession of the Royal Aeronautical Society, which they have made available online. We show the titlepage (fifth image) and one of the drawings (sixth image).

Henson and Stringfellow spent the next three years building and trying to fly a 1/7 scale model of the Ariel. They were not successful. The model flew well enough when travelling down a suspended wire, but when it left the wire, it did not have enough power to generate the lift needed to keep it in the air. Finally, after three years of trying, Henson gave up. He moved to the United States in 1849 and invented a few things, but his aircraft days were done. Stringfellow carried on without him, and in 1848, was able to get a new model to fly in an empty warehouse in Chard, the first successful flight of any kind of heavier-than-air powered lifting body. Town officials commissioned a sculpture of Stringfellow's model for the town square in Chard, with no mention of Henson. We will show it to you when we do a post on Stringfellow.

I think Henson’s original model of 1844-47 survives in the Science Museum, but I cannot find it on their website. There are several photos of it in the excellent study of Henson and Stringfellow written by M.J.B. Davy and published by the Science Museum in 1931 as Henson and Stringfellow: Their Work in Aeronautics (this book also provided the colored reproduction of the 1843 engraving that we show in our third image). The model did not come to the museum until the 20th century and had been heavily restored when they acquired it. The National Air and Space Museum in Washington has what they call a copy of Henson's original model, but it was made in 1921, and I am not sure what exactly was copied (seventh image). But at least I could find it on the NASM website. It does vaguely resemble the drawings in Henson's Specifications of 1843 (sixth image).

There is only one portrait of Henson, a photo showing him 40 years after he conceived the Ariel. It is supposed to be in the Smithsonian portrait collection, but I could not find it there, and had to settle for the Wikimedia version (second image). Henson died in 1888 at age 75, and is buried in Rosedale Cemetery, Montclair, New Jersey. I could find no photograph of his gravestone, if there is one.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“The First Carriage, the Ariel [over Egypt],” lithograph by Thomas Picken, 1843, British Museum (britishmuseum.org/collection)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/45e67b9b-3b1c-4cc6-926d-0e7cf9700ec8/henson4.jpg?w=800&h=517&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)