Scientist of the Day - Thomas Sopwith

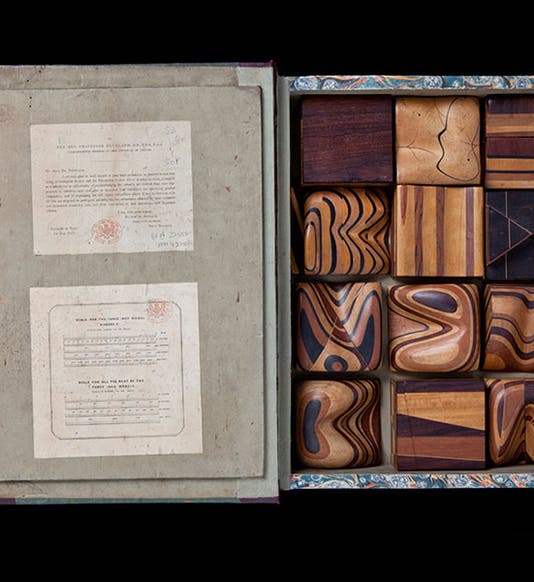

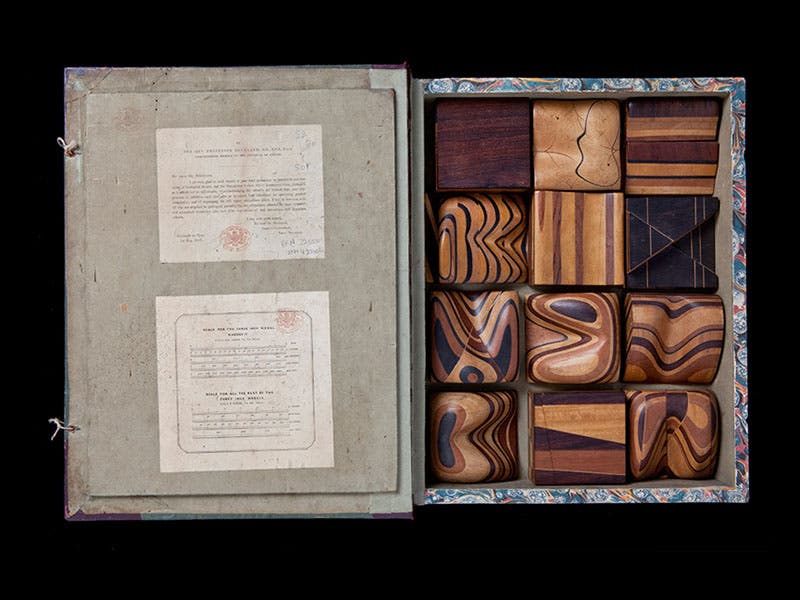

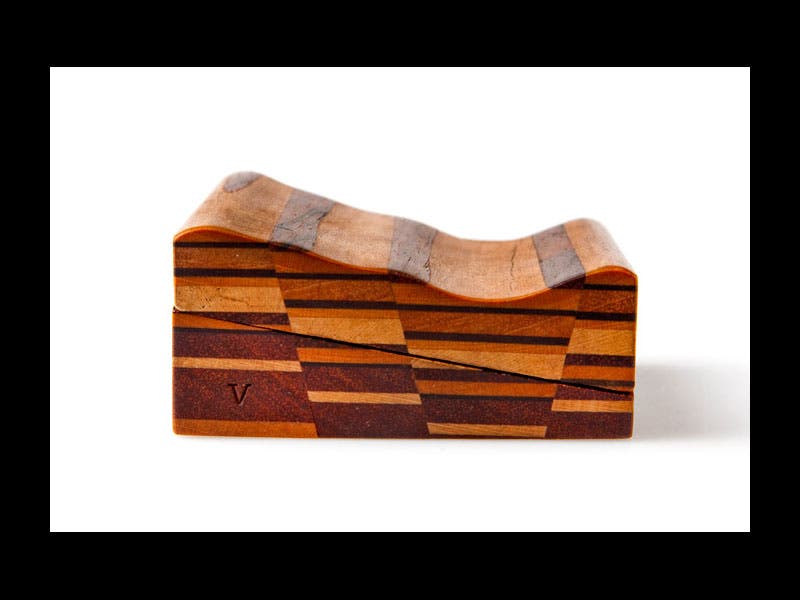

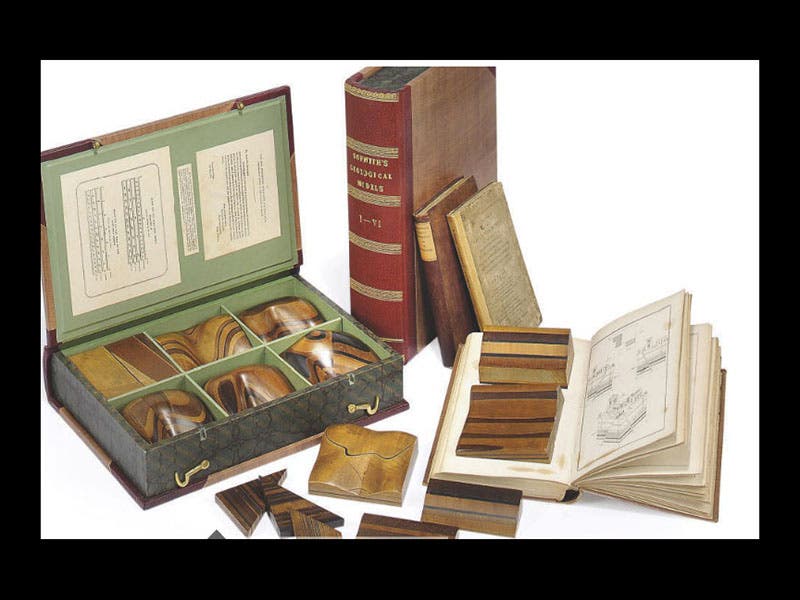

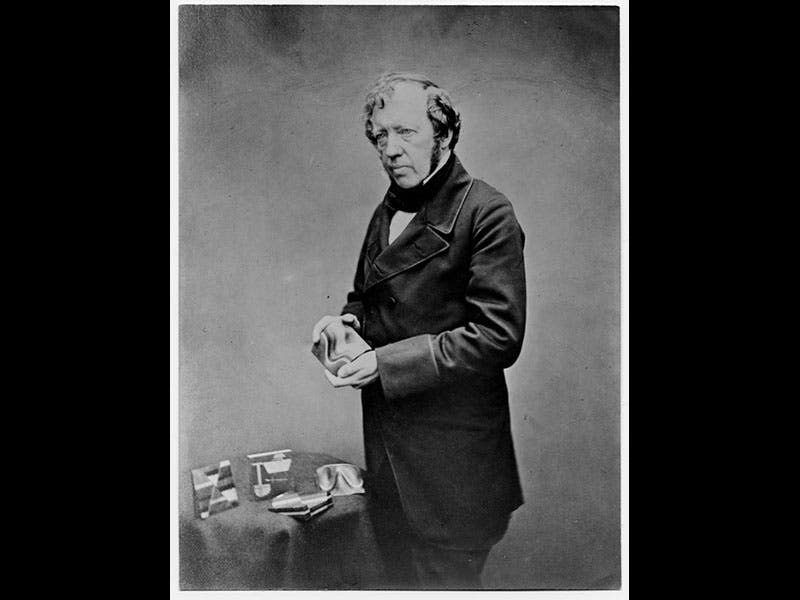

Thomas Sopwith, an English geologist and mining engineer, was born Jan. 3, 1803. Thomas' father was a cabinet maker, and Thomas thought of making that his own career, entering into an apprenticeship, before giving up woodworking in favor of geology and mining. Ordinarily, cabinet making is not too useful for a geologist, but in Thomas's case, it was just the ticket. Around 1840, Sopwith got the idea of making geological models for instructional use, where the layers of rock are represented by different kinds and colors of wood. He visited William Buckland, the prominent geologist at Oxford (and the discoverer of the first dinosaur), who gave him feedback about what kinds of models would be useful in the classroom. In 1841, Sopwith went into production. He manufactured dozens of different kinds of stratigraphic models, sculpted out of wood, and sold them, packaged into boxes disguised to look like thick books. They were apparently quite popular--sets survive today in the Whipple Museum and the Sedgwick Museum at Cambridge, at the Oxford Museum, and at the Natural History Museum in London (first image). We also show one of the individual models, depicting dislocation of strata (second image). A set sold at auction at Christie’s in 2000, bringing a sizable sum (third image). One of the few surviving photos of Sopwith shows him presenting his models (fourth image).

Sopwith is noteworthy on at least two other counts. First, he kept a personal diary for over 57 years. In 1891, his diary was edited and published--edited not because it was naughty, but because it was long--57 years long--and we have this work in the Library, in its shiny dark blue Victorian cloth. I read the entries for the years around 1841, when the models came out, and his daily life was just fascinating, as he travelled incessantly to consult on mining operations. Whenever he was in London or Oxford, he dined every night with distinguished men like Charles Babbage and Charles Darwin, or men who would later become distinguished, like John Ruskin. Sopwith described in detail what life was like at Buckland's home in Oxford, where the entire house was a museum of rocks and fossils, and was also crawling with live animals, lizards and hedgehogs and such, with the five young children always underfoot, and he found the entire tumultuous scene absolutely delightful, as does indeed the modern reader.

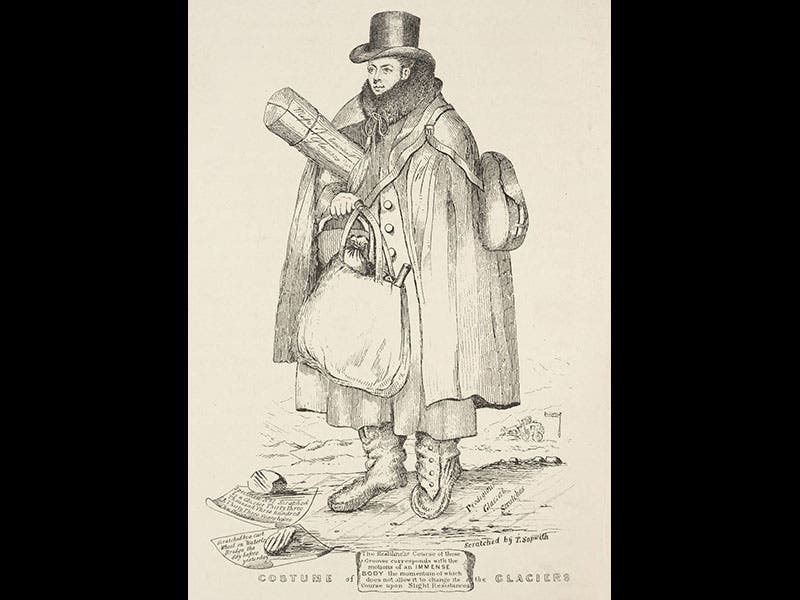

The other interesting feature of Sopwith's career is his artistic ability. Not too many examples of his artwork are extant, although his contemporaries all praised his drawings. But one sketch does survive, a cartoon of his friend Buckland (fifth image). Sopwith accompanied Buckland and several other geologists on an excursion into the Scottish highlands in 1840, just after Louis Agassiz had argued that glaciers once covered all of northern Europe, including Scotland. Evidence for previous glacial presence could be found in parallel scratches on the rocks, made when a glacier passed over. The excursionists found parallel scratches everywhere, revealing that Agassiz was right about Ice Ages. The cartoon shows Buckland, carrying his maps and comestibles for the hike, and the various captions at the bottom identify scratches caused by glaciers, scratches caused by horse carts, and scratches caused by sketch artists, for the print is signed at bottom right: "Scratched by T. Sopwith”.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)