Scientist of the Day - Joseph Bazalgette

Joseph Bazalgette, an English civil engineer, was born Mar. 28, 1819. In 1856, Bazalgette was appointed chief engineer to the London Metropolitan Board of Works. The Board's predecessor, the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, had been wrestling with London's massive sewage problem, without success, as there was not much agreement as to what to do. In those days, much of the sewage was dumped right into the streets, and where there were drainage systems, they emptied directly into the Thames. The tidal flats of the Thames were awash with sewage whenever the tide went out. Bazalgette would no doubt have run into considerable opposition to any kind of a universal sewer system, were it not for the coincidental occurrence of the 1858 "Great Stink". The weather was extremely hot that summer, and the stench was unbearable. The Houses of Parliament, which sit right on the river, suffered through intolerable conditions, and then in desperation, Parliament passed a sewage act, with funding, and Bazalgette got to work.

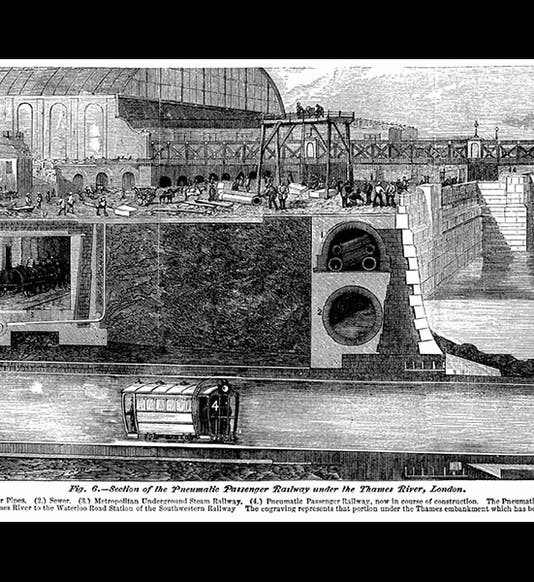

Bazalgette’s crews built over 80 miles of underground brick sewage tunnels in London, and at least a thousand miles of street sewers to feed the tunnels. He laid out three parallel lines north of the river, which took sewage to the east, far downstream of London, and two south of the river that did the same thing. The most noteworthy line was the so-called "interceptor line", which ran just north of the river and intercepted all the sewage lines that heretofore had drained straight into the Thames. To house the sewage tunnel as it ran along the river, Bazalgette opted to build a massive embankment, then called the Thames Embankment, right on the edge of the river. The embankment would cover up the unsightly mudflats, house the sewer line, utility lines, and an underground railway, and provide as a bonus a broad top surface suitable for a carriage road and pedestrian pathways. You can see above a contemporary engraving, showing a section through the embankment (first image). In addition, Bazalgette built four massive pumping stations to move the sewage along; some of these were works of art in their own right.

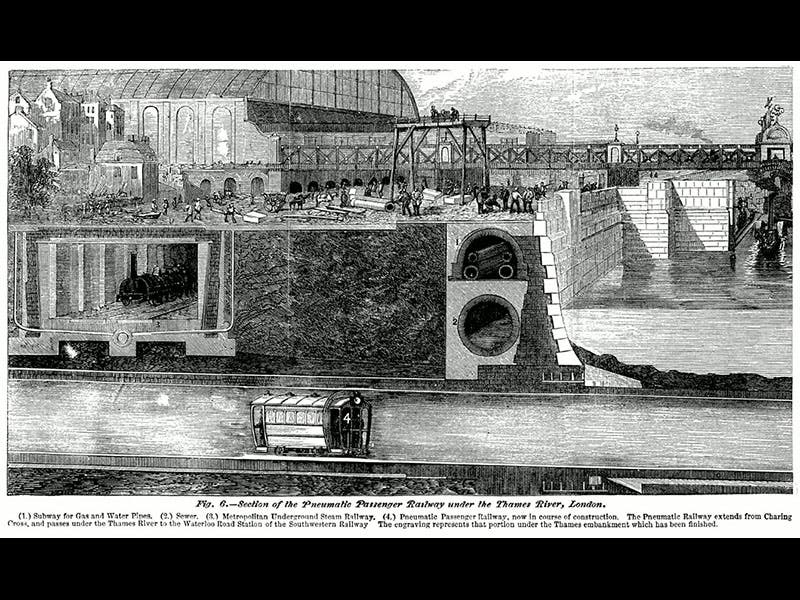

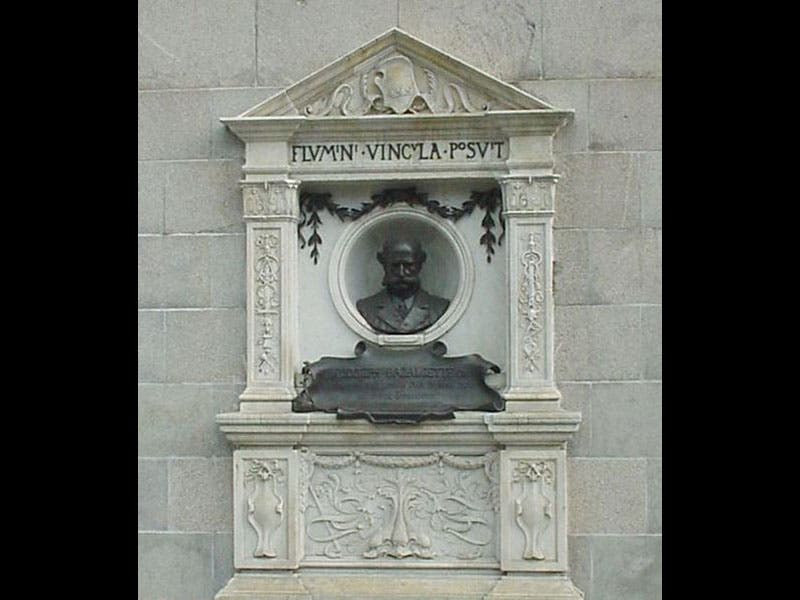

The London sewer system was opened by the Prince of Wales in 1865, although the embankments would not be finished until 1874. In due course, the embankment north of the river, between Westminster and Blackfriars Bridge, would be named Victoria Embankment, the shorter stretch south of the river would be called the Albert Embankment, and the stretch just upriver, in Chelsea, the Chelsea Embankment. Above is a view of the Victoria Embankment taken about 1900 (second image). The embankments are still one of the hallmarks of central London, their charm considerably augmented by the sturgeon lampposts designed by George Vulliamy and set in place when the Victoria Embankment opened in 1870 (third image); see the SoD for May 19, 2015.

One of the unexpected spinoffs of Bazalgette’s new metropolitan sewer system was the disappearance of cholera from London. Although John Snow in 1854 had demonstrated that cholera epidemics could be traced to wells polluted by sewage, no one paid him any attention, and most medical authorities preferred to believe that miasmas, or polluted airs, were the main cause of cholera. But once the London sewage was contained, cholera epidemics vanished from the city.

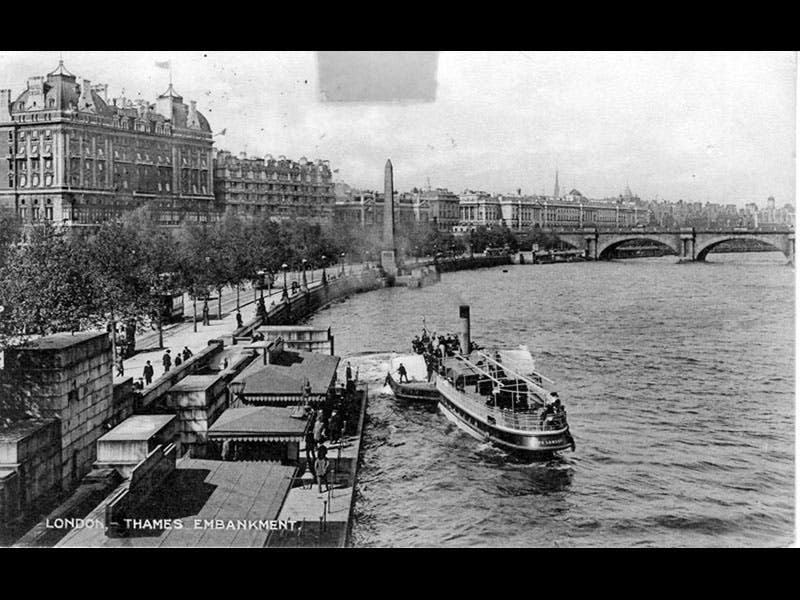

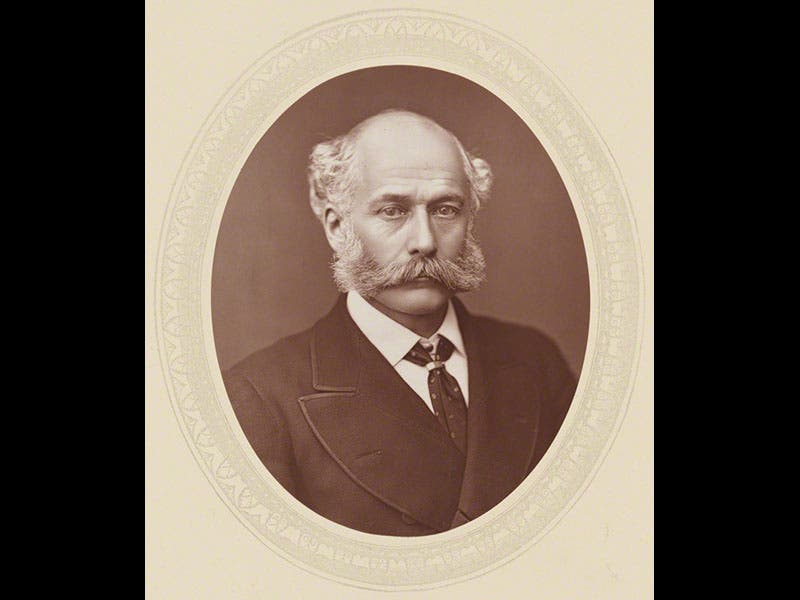

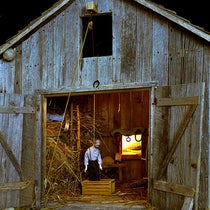

Bazalgette built his sewer system so well, and with such foresight, that it still serves London today, with virtually no changes; we see above a modern photo from the Victoria Embankment (fourth image). Bazalgette was knighted in 1875, and there is a memorial bust on the Victoria Embankment (fifth image). And a lovely Woodburytype portrait of Bazalgette may be seen in the National Portrait Gallery (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.