Scientist of the Day - John Jervis

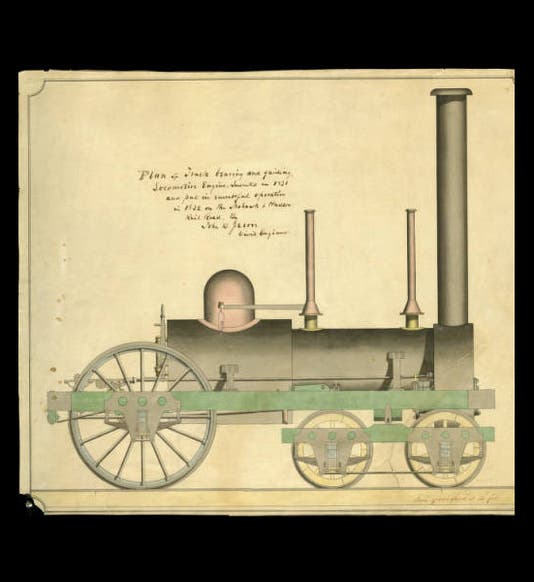

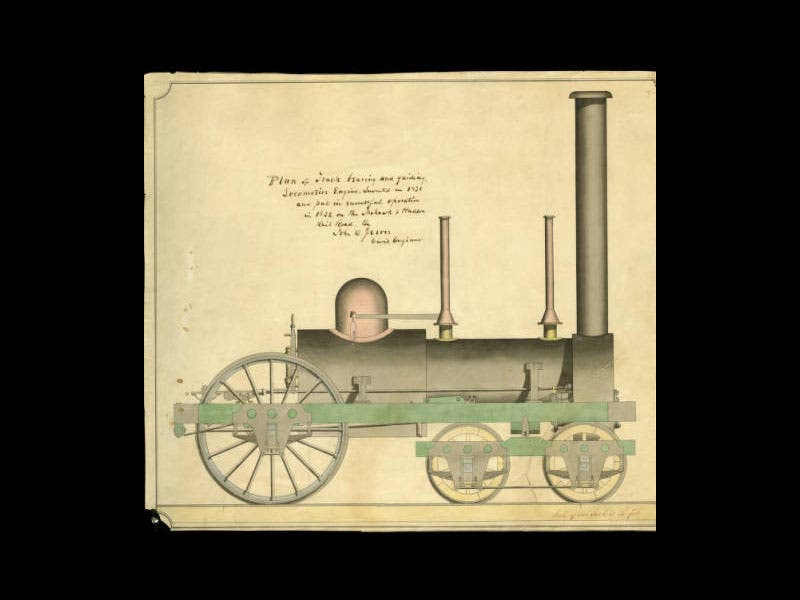

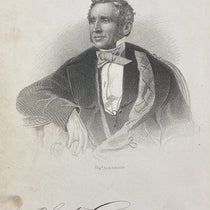

John Bloomfield Jervis, an American engineer, was born Dec. 14, 1795. Jervis was multi-talented, contributing to mechanical engineering, civil engineering and, through his estate, public education. Jervis became chief engineer for the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad in 1827, before there was a single mile of track in America. After the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was launched in England in 1830 (the first public railroad anywhere), Jervis imported one of their locomotives to the U.S., but found it was too heavy and could not negotiate the tight turns of American right-of-way. So he designed and built his own engine, called the Experiment. The novelty of his engine was in the mounting of the wheels; he cut the drive wheels down from four (on two axles) to two (on one axle), and he added a swivel four-wheel truck at the front to lead the locomotive around curves. It was the first 4-2-0 locomotive ever, and it served as the prototype for most American engines for decades, because it could negotiate just about any track. We see above Jervis’s original drawing for his 4-2-0 (first image), and a photo of a historic 4-2-0 (built in 1837, imitating Jervis) that is in the Chicago Museum of History (second image).

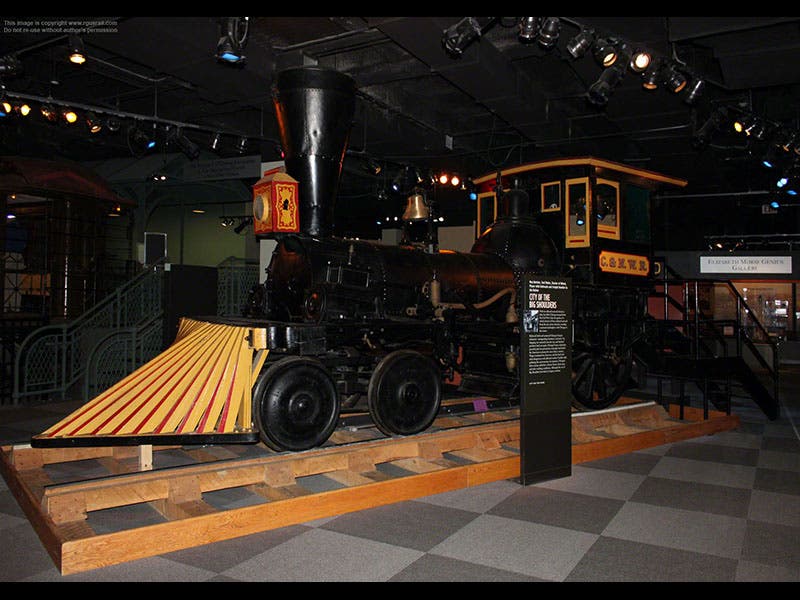

In 1836, Jervis was appointed chief engineer on the Croton Aqueduct project. The aqueduct was to carry water to New York City from the Croton River Dam, some 40 miles away. The construction project involved building the dam, designing several tunnels, a slew of culverts, and a few bridges, with the major bridge spanning the Harlem River, and then constructing everything. It took Jervis only 6 years to accomplish all tasks; the aqueduct opened on Oct. 14, 1842, immediately delivering thirty-five million gallons of water per day to the city. We see above the Harlem High Bridge, part of the aqueduct (third image).

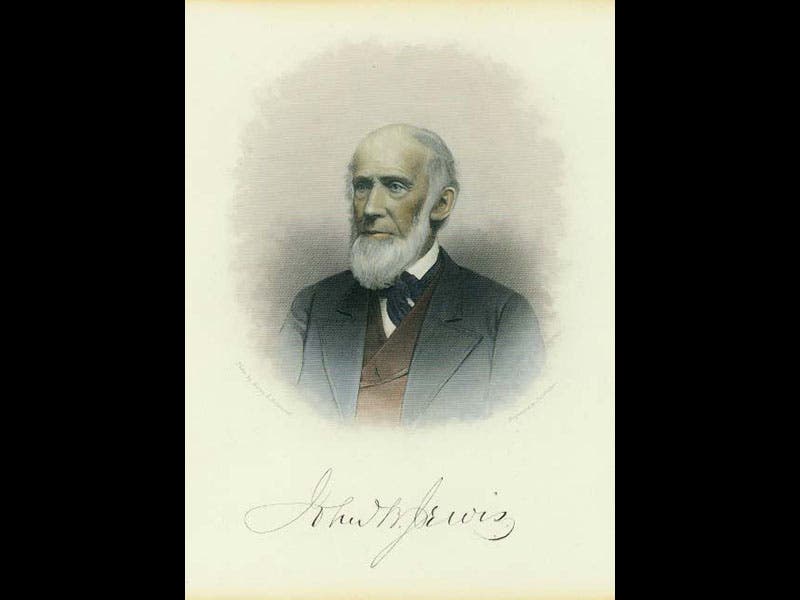

When he died, Jervis left his entire library of 8500 books and his house to his home town of Rome, in up-state New York. The Jervis Public Library still serves the community and houses Jervis’s books and papers, including the first image above (fourth image). There is only one good surviving portrait of Jervis, but it is exceptional (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.