Scientist of the Day - Earl Douglass

Earl Douglass, an American paleontologist, was born Oct. 28, 1862. In 1902, Douglass joined up with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. The Museum had been founded by Andrew Carnegie in 1895, but it only acquired its first dinosaur, Diplodocus carnegiei, in 1901, the year before Douglass came on staff. Douglass’s job was to find more dinosaurs out west, and after making a number of small discoveries, he struck the mother lode in August of 1909, when he chanced upon the tail bones of what turned out to be the most complete skeleton of Apatosaurus (Brontosaurus, if you prefer) ever found. The Carnegie Museum staked out the site of the discovery, which was near Vernal, Utah, just across the border from northwestern Colorado, and it became known as the Carnegie Quarry. Douglass was assigned to work there year round, so he moved his family out, bought a ranch nearby, and spent most of the rest of his life there (he died in 1931). First he finished excavating the Apatosaurus, and in 1915 it was erected in Dinosaur Hall in the Carnegie Museum, right next to Diplodocus carnegiei. Douglass’s dinosaur was formally named Apatosaurus louisae, after Carnegie’s wife Louise. We see above a photo (first image) of Dinosaur Hall taken around 1930--Douglass's Apatosaurus is on the right. Dinosaur Hall was completely remodeled in 2005, but when they re-opened the doors, the two giant sauropods stood where they had always stood, although they are now wallowing in greenery and taking some notice of each other (second image). Apatosaurus is still on the right, but he is now exchanging glances with “Dippy,” as Carnegie always called his Diplodocus namesake.

The Carnegie quarry became Dinosaur National Monument in 1915, although the site continued to be worked until 1925. When Andrew Carnegie died (1919) and the Carnegie Museum ceased to dig at Vernal, Douglass quit and went to work for the University of Utah--new employer, same site. In 1923, he turned up a large part of a skeleton known as Barosaurus lentus, a very rare species of sauropod. The skeleton was somehow divided up among 3 different museums, but in 1929 all the parts were acquired by the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. The bones sat there for half a century, and then the museum unveiled a spectacular mount, right in the atrium entrance to the dinosaur exhibits (third image). Douglass's Barosaurus stands reared up on its hind legs, its head 45 feet in the air, trying to protect its skeletal young from a skeletal theropod. The mount is made of fiberglass, since the real bones are too heavy to mount in such a fashion, but the Museum does have the bones--Douglass's bones--to back up their mount.

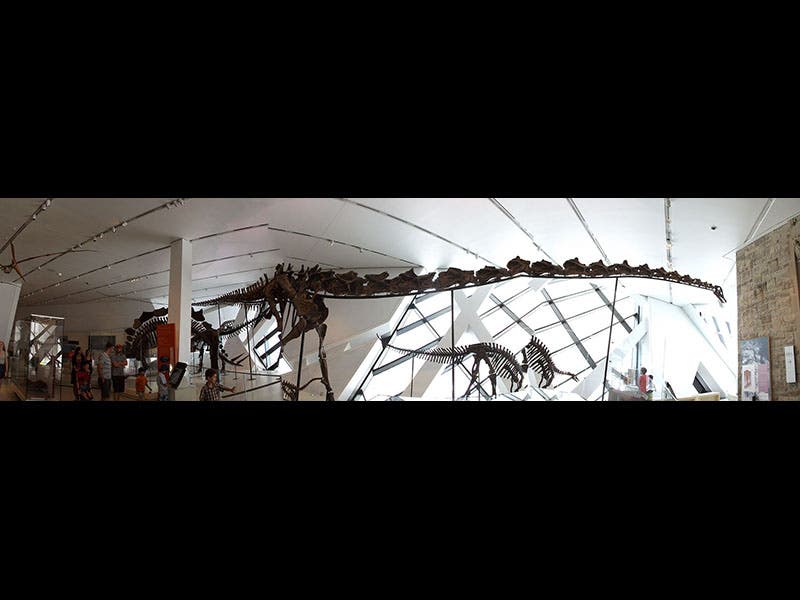

There is another Barosaurus mount in North America, and Douglass found this specimen as well. It stretches across a considerable portion of the floor in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (fourth image), and it is really just a spectacular as the AMNH mount.

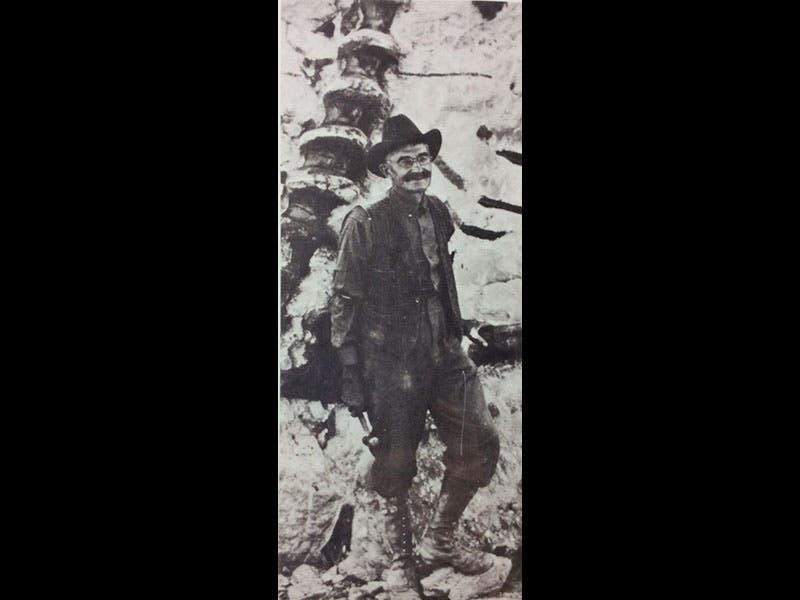

The portrait of Douglass (fifth image) shows him at Carnegie Quarry around 1908, standing in front of a Diplodocus skeleton that is about to be excavated. He looks like a man who is very pleased with his chosen occupation.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.