Scientist of the Day - Pan-American Exposition

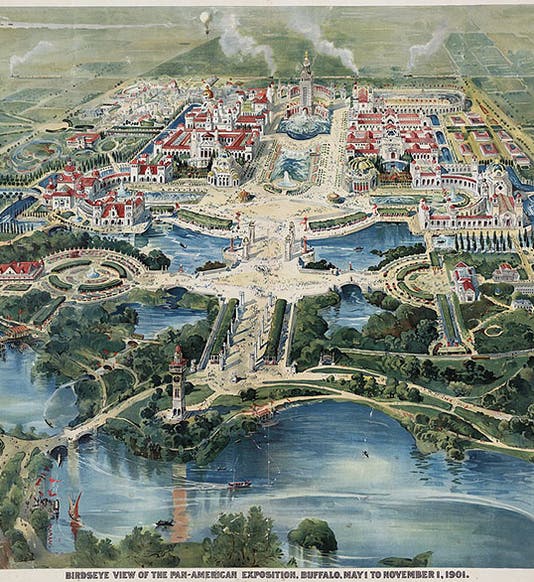

May 1 was apparently a popular day to open a world’s fair. The World’s Columbian Exposition had opened on the Chicago Midway on May 1, 1893. Eight years later, in 1901, the Pan-American Exposition opened on the same day in Buffalo, New York. This fair was not quite as large as the Chicago World's fair, but it was bigger than most, bringing in some 8 million visitors in the six months it was open (the Chicago fair had drawn 26 million). It certainly had a beautiful setting, as a poster attests (first image).

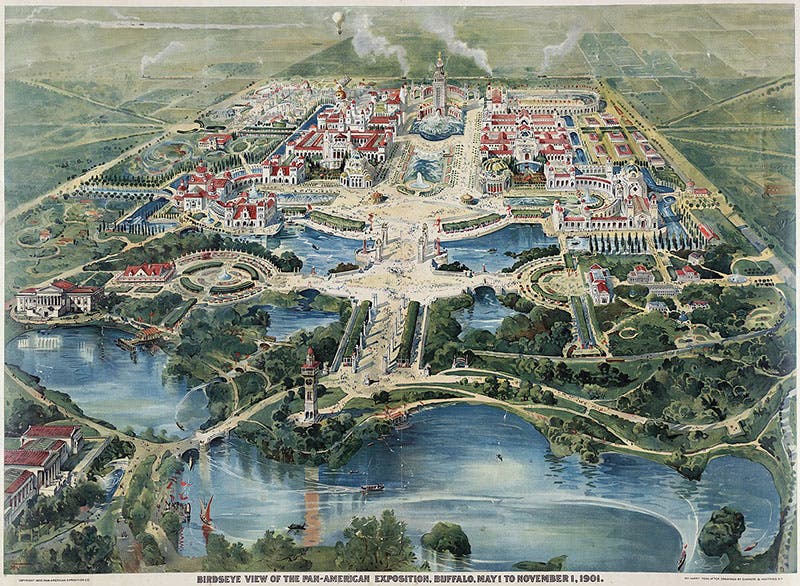

The fair’s most famous structure was the Electric Tower, the tallest feature visible in the poster, powered by the new Westinghouse-Tesla alternating current system, which enabled the electricity to be generated 40 miles away at Niagara Falls and brought in on high-voltage lines. A night-time panorama captures the spirit of newly electrified America (second image). The fair has unfortunately earned notoriety because it was there, on a September afternoon in 1901, that President McKinley was assassinated. But if should be remembered as well for its many novelties.

We prefer to remember the Pan-American Exposition for its commemorative stamps. The stamps issued for the Columbian Exposition in Chicago had remembered the past – Columbus and the Age of Discovery. The Pan-American stamps celebrated America’s technological future, commemorating lake steamers, ocean liners, locomotives, electric automobiles, canal locks, and the Niagara Falls arch bridge.

The stamps were issued in denominations of 1¢ to 10¢ (none of those $5 stamps like they had at Chicago, useless for postage and good only for fattening the coffers of the Post Office). Belying their magnified appearance on your monitor, the stamps are quite small – much smaller than modern commemoratives – and must have been a challenge to engrave. The designer and engraver was the mysterious Raymond Ostrander Smith, who exploded onto the postal scene in 1898, designing the commemorative stamps for the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha that year. Then he did the Pan-American stamps in 1901, and subsequently a series of presidential portraits in 1902. With that, he abruptly quit the Bureau of Engraving and went back to work for a private firm, leaving in his wake three of the finest series of stamps ever engraved. We have written a post on Smith, where we showed the 2¢, 4¢, and 5¢ Pan-American Exposition commemoratives (as well as his famous “Black Bull” of 1898, his most praised stamp). Here we show the 1¢, 4¢, 8¢, and 10¢ Pan-American stamps (third-sixth images), as well as a composite of the entire set (seventh image). All of the images come from the National Postal Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The Pan-American Exposition commemorative stamps were the very first U.S. postage stamps to be printed in two colors – black, combined with blue, red, brown, or green. When you print in two colors, there is always the chance that a sheet might be reversed on its second run through the press, producing what philatelists call an "invert" – a stamp where some feature is printed upside down. In this instance, three of the denominations produced inverts – we show here an invert of the 2¢ stamp, where the Empire State Express Train is upside down (eighth image).

Inverts are embarrassing for the Post Office, but they greatly excite collectors, since the inverts are very scarce and highly collectible. In 2009, a block-of-four of each Pan-American invert sold at auction for a total of over $1.1 million, with the 2¢ block-of-four invert alone – the scarcest of the three – bringing the hammer down at $800,000. This might be a good time to check the stamp collection that you had when you were a kid, if you were part of the generation that collected stamps, as I was. I have two of the Pan-American stamps. But, alas, on my 2¢ stamp, the Empire State Express rides on the rails, not under them

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.